With more and more vehicles employing a turbocharger to achieve power and fuel efficiency from a downsized engine, the importance of maintenance is more critical than ever. Up to 50% of turbocharger failures are due to oiling problems, which can result from the lack of lubrication or not cooling down enough after the engine is shut down.

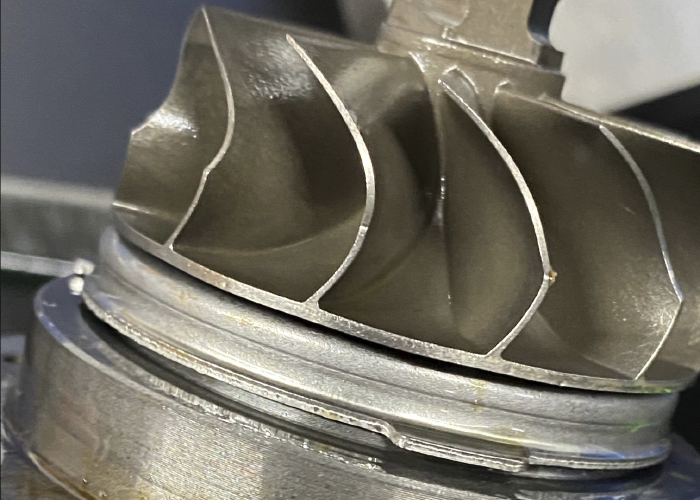

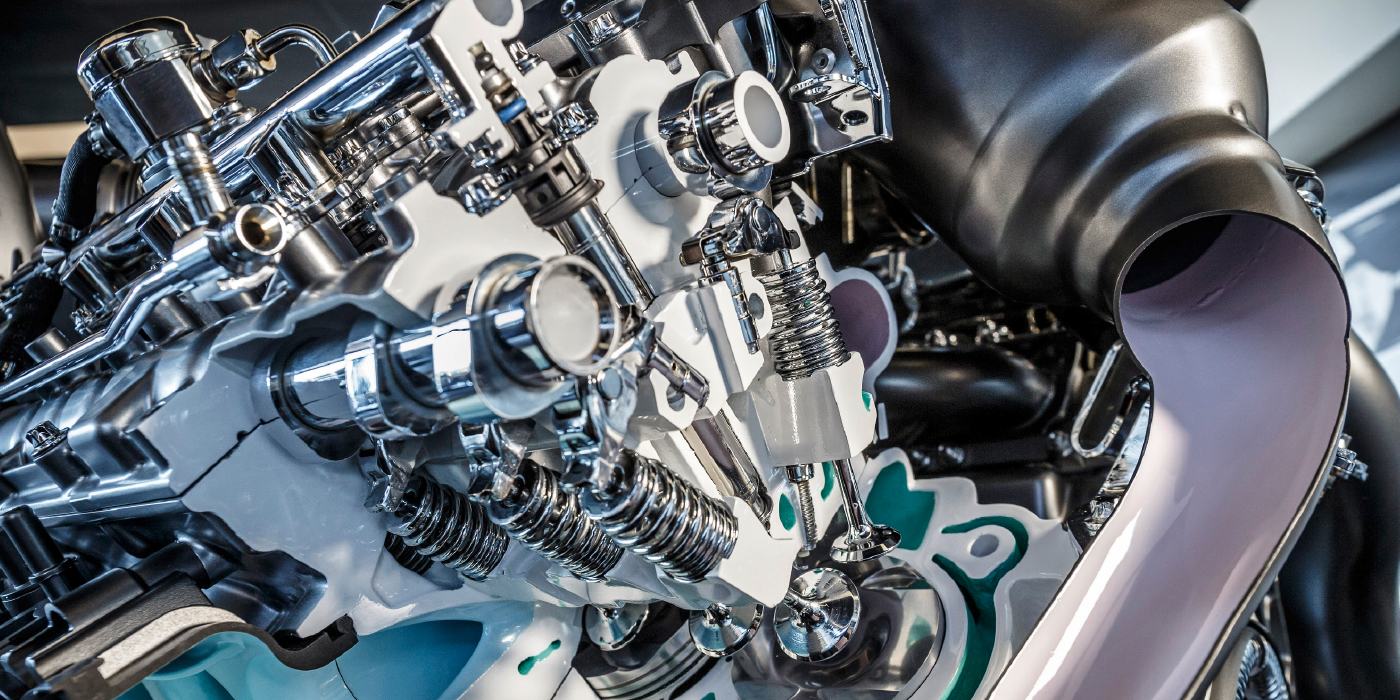

Today’s turbo systems are designed to reach maximum boost pressure with minimal lag time. Some OEMs are using smaller turbos that spool up quicker and reduce lag time, but they also run hotter the more rpm they turn. Most modern turbochargers use a “plain” bearing system to control the main bearing shaft’s movement.

There is a thin film of high-pressure oil supporting the shaft so that it floats while it rotates. Despite the film of oil that creates an oil wedge for the bearing to ride on, modern turbos can rotate at more than 240,000 rpm, or 4,000 rotations per second, and build up heat quickly to move the air.

Turbos need good lubrication and cooling to handle the stresses of high rpm and everyday driving, which is why many manufacturers recommend synthetic oil because it can better handle higher operating temperatures without breaking down. If your customers are not doing regular oil and filter changes, it can lead to varnish deposits, sludge and, ultimately, bearing shaft failure.

Of course, some turbo failures are not the result of a lack of maintenance. Some failures are due to faulty manufacturing (although very few). Nissan, for example, issued a recall for certain 2011 Jukes due to a defective weld on the boost sensor bracket. Nissan says the weld may break and separate the air inlet and cause the vehicle to stall. One Juke owner had to replace the engine and the turbo because the turbo blew shards of metal into the oil line and subsequently destroyed the engine in the aftermath.

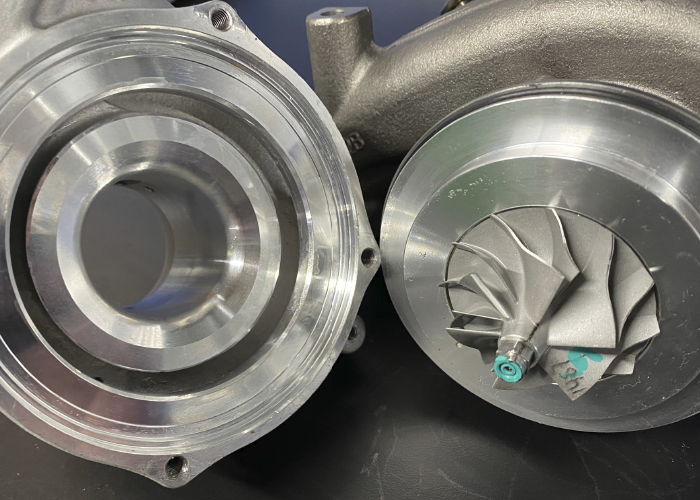

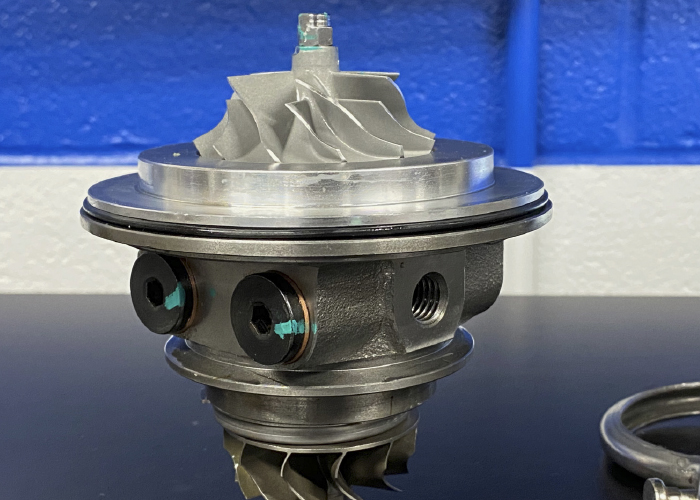

Rebuilt Units

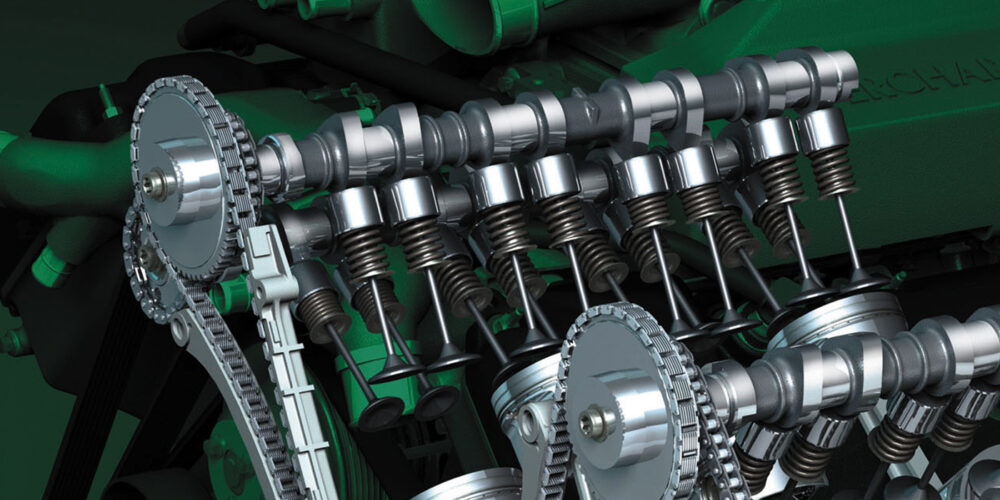

A rebuilt turbo may be an option on some vehicles, but many will need to be replaced with an OE unit, which is a lot more expensive. Either way, it’s a good idea to tear apart the turbo to get to the bottom of the situation and to keep it from happening to the new one. The shaft bearings are usually the first thing to check if a failure is suspected. If the shaft was out of balance or oil starved, it may exhibit the telltale signs of damage like grooving, pitting or caked-on oil. It may not spin freely due to bearing damage or a broken compressor wheel.

Turbos that are water-cooled feed coolant through the center housing around the bearing shaft. The bearings also rely on the supply of oil for lubrication so they don’t get too hot and cause oil coking at normal operating temperatures.

When the engine is shut off, the turbo still needs to cool down. If not, it can heat-soak the housing and oxidize the oil, forming coke deposits that act like an abrasive to wear the bearings. Installing an auxiliary oil cooler and changing the oil every 3,000 miles can prevent oil breakdown and coking problems. In water-cooled turbos, coking is less of a problem, providing the oil is changed regularly and quality engine oils are used, such as a synthetic or one for high temps.

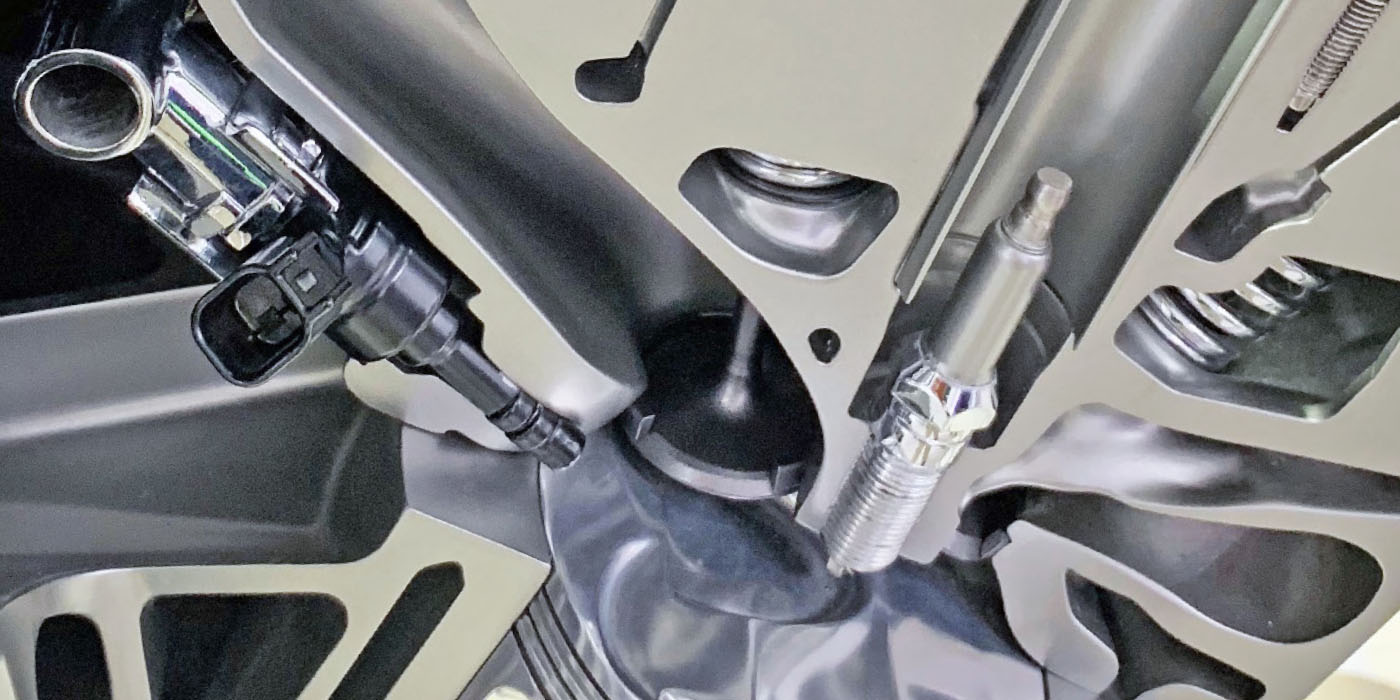

If the oil supply to the turbo is restricted during high-speed operation, even for a second, the buildup of heat can cause contact between the shaft and bearing surface and eventually lead to shaft seizure, and a death sentence for the turbocharger.

If oil starvation is suspected, check for a low oil level, oil leaks or a restriction between the turbo and engine, or low oil pressure. Idling the engine for a few minutes to allow the turbo to cool down can prevent oil starvation. An aftermarket oil accumulator can also be used to keep the oil pressure up for a minute after the engine is turned off. These systems are also good for preventing dry starts and serve as additional insurance against turbo failures.