For me, sourcing automotive chemicals and motor oils goes all the way back to 1957 when I worked at my corner service station. Since we were a small town without a local parts jobber, we bought our oil additives and chemicals from an out-of-town distributor. Our gasoline and motor oil came from our local-branded petroleum products distributor. We bought independent motor oil labels from various wholesalers by the case. To save our customers money, we hand-pumped most of our company-branded motor oil from barrels into one-quart glass oil bottles topped with pointed oil pour spouts. Such was the technology and practice of those days.

The ’50s: (Not So) Happy Days

Since early oil ratings weren’t truly reflective of oil performance, our primary concerns about motor oil were whether it was detergent or non-detergent, straight-weight or multi-viscosity. Through experience, we found that some oil brands would quickly oxidize and cause varnish to form in the new engines equipped with hydraulic lifters. The lifters would stick and become noisy, to the extreme irritation of many new car owners.

In other instances, the motor oils and gasolines of that era left hard carbon and lead deposits in the cylinder head and valve ports, which would shorten valve life. Similarly, oil sludge would accumulate and clog the engine’s oil pump screen and oil galleries. The result of excessive cylinder head deposits and poor lubrication was that many engines of that era rarely lasted more than 70,000 miles without a major valve or connecting rod bearing failure. It goes without saying that our selection of motor oils was based not upon oil ratings, but upon our collective experience with the various brands.

Today’s Standards

Today, increasingly stringent refining standards have complicated the sourcing of engine oils. To illustrate, while the American Petroleum Institute (API) ratings have served as the industry standard for many generations, newer standards such as those represented by the International Lubricant Standard and Approval Committee (ILSAC), the European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA), the Japanese Automobile Manufacturers Association (JAMA) and the Korean Automobile Manufacturers Association (KAMA), are now appearing upon oil bottle labels.

Getting Rated

In addition to the API, ILSAC and ACEA ratings listed on most engine oils, some auto manufacturers are now adding proprietary ratings for oils that are engineered for specific engine applications. There are several reasons for this.

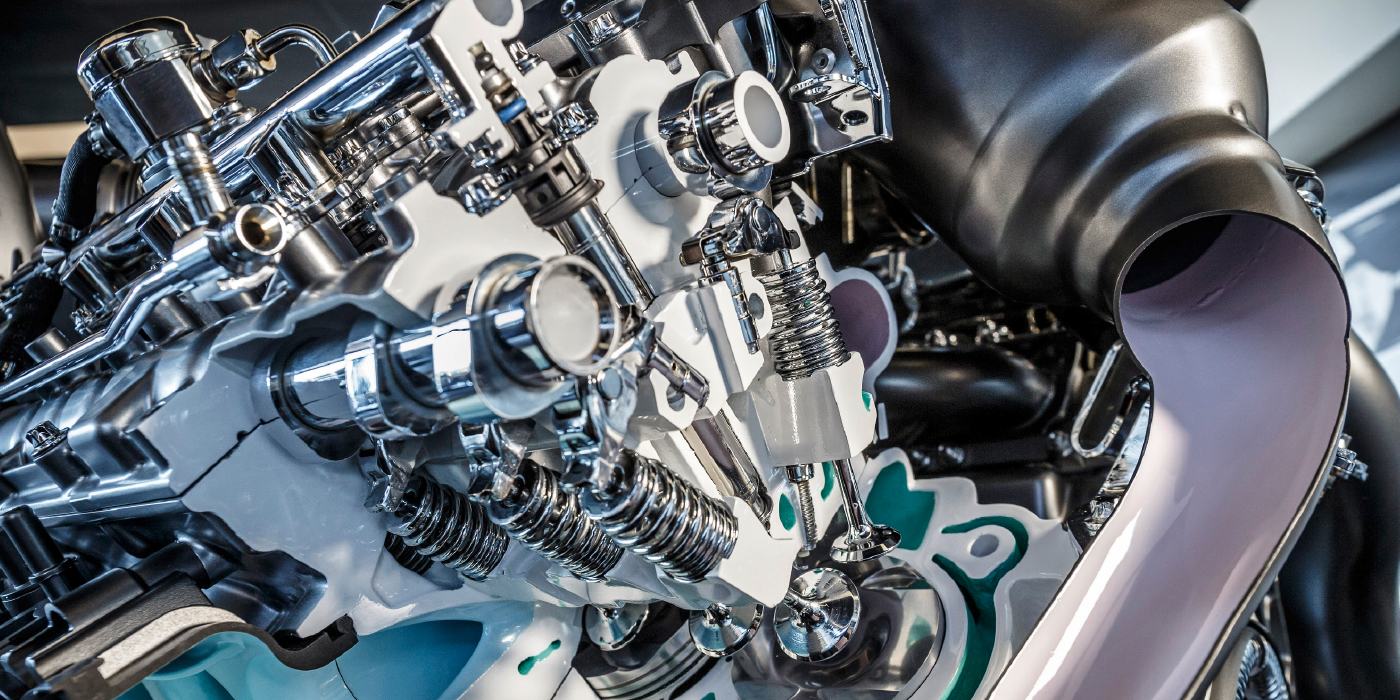

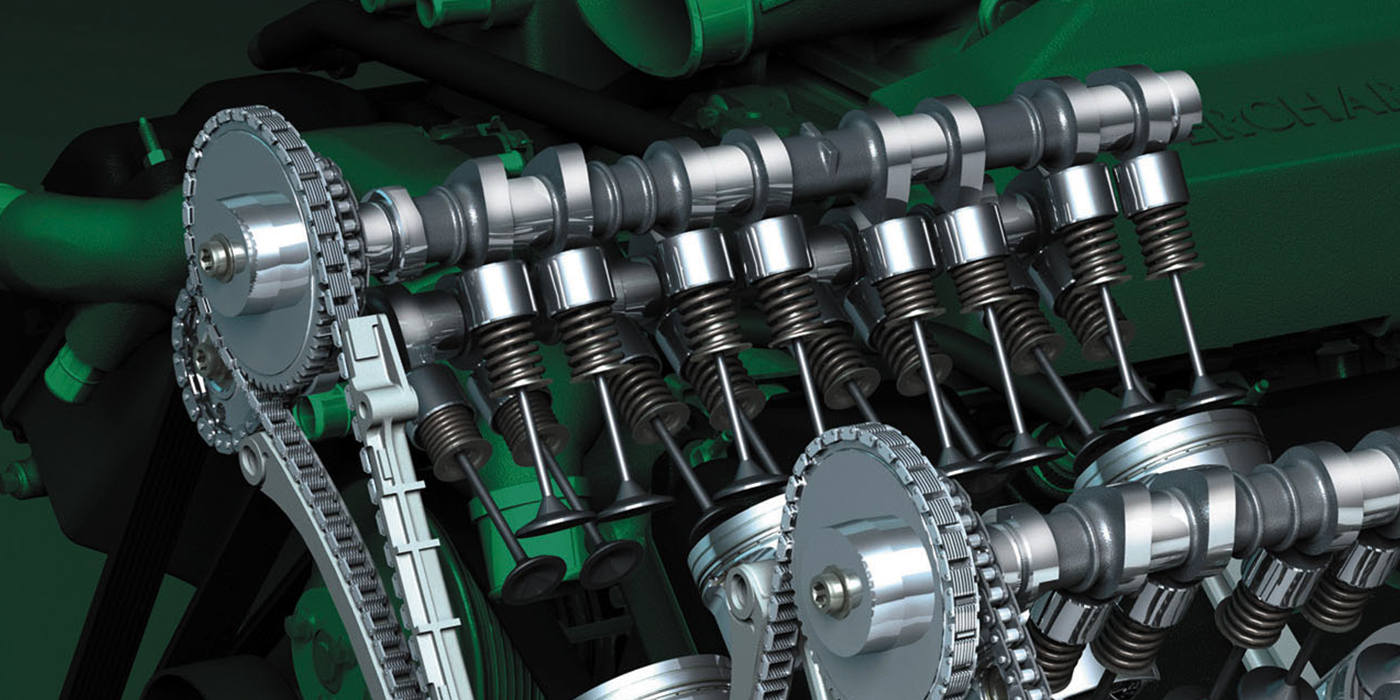

First, anti-scuff additives drastically shorten catalytic converter life. Second, overhead camshaft engines are designed with less reciprocating weight in the valve train, which reduces stress on the camshaft lobes and thus reduces the need for anti-scuff compounds.

Third, engines may tend to form crankcase sludge earlier because engineers have fine-tuned air metering into the engine by reducing positive crankcase ventilation system flow. In addition, some cylinder head designs may run hotter, which increases oil temperatures and hastens oil oxidation. Oxidation causes the oil to varnish internal engine surfaces and “gel” into a viscous fluid resistant to flow.

Last, many manufacturers are increasing oil change intervals, which further exacerbates the demands upon any engine oil. As a result, engine oils must meet not only API, ILSAC and ACEA standards, but also the auto manufacturer’s proprietary ratings.

Incompatible Lubrication

A recent instance in my own shop involved something as simple as buying automatic transmission fluid for a high-end Asian vehicle. Looking over the service data, I found that the “type 2” fluid originally installed in the vehicle had been replaced by the latest “type 4” fluid. A technical service bulletin stated that the two fluids should not be mixed.

A transmission fluid was available from my local jobber that would meet the OE specifications. Was this specification meant to be a “top-off” specification or a “refill” specification? The difference can be critical on a $3,000 automatic transmission.

Tech’s Influence

The tech is the person ultimately responsible for choosing the correct lubricant for a specific application. (See chart on page 14.) Meeting the conditions of extended warranties also makes the correct choice of lubricants even more critical for the DIY or installer. Consequently, it’s extremely important for any technician or service manager to check the owner’s manual and applicable technical service bulletins for correct lubricant information. In most cases, the local jobber can supply the correct lubricants. For many proprietary applications, however, the nameplate specialist may find himself buying OE-spec lubricants directly from his local dealership.

Needing a Chemical?

As I stated at the outset, the oil and fuel additive industries were built on the premise that early engines accumulated huge amounts of carbon in the cylinder head and sludge in the crankcase. However, assuming that maintenance schedules are followed, most modern engines don’t require oil additives to keep the internals of the engine clean and well-lubricated.

Of course, the tech is always faced with an engine that hasn’t been maintained and is in need of internal cleaning and lubrication. When used as directed, most name-brand oil additives will perform that task in an efficient and cost-effective manner. The danger is that the engine is sludged well beyond the point of remediation with an oil additive. In this case, the engine should be flushed, repaired or replaced.

As for fuel additives, many engines driven in slow-moving traffic can develop clogged injectors and carbon buildup on the valves. Low-quality gasoline contributes to the clogging and carbon buildup until the engine begins to perform sluggishly or runs roughly enough to cause a misfire condition. In addition, a fuel additive may be required to remove excess moisture from the fuel tank.

Whatever the need, some shops use additives on an occasional basis and others, such as a fleet or professional repair shop, might use them for preventive maintenance.

Meeting the Needs of Customers

Obviously, the professional oil, additive and chemical markets are becoming much more complex. Whereas the DIY market might be more price sensitive, the professional market is becoming more performance sensitive. Sure, the professional still wants the best price, but he also wants oils, additives and chemicals that meet the needs of his customers.

Once a professional finds a brand of oils, additives and chemicals that perform, he usually continues to demand that brand. In addition, he needs additives to meet specific needs, like loosening sludge from a neglected engine or softening seals on a high-mileage transmission. Or he may need a special throttle cleaning chemical that cleans throttle body plates without destroying delicate throttle sensors, shaft seals or non-stick coatings. He may also need an electrical cleaner that removes dirt and oil from delicate electronics without ruining plastic connectors. The needs are infinite and the market is there, providing a jobber identifies those needs and can act as a source for quality products that will meet those needs. As in the earliest days of the automobile, oils, additives and chemicals will continue to be a major part of today’s professional installer market.

| Q: What is the importance of oil “viscosity”?

A: The “viscosity” rating of a motor oil is how easily it flows at certain temperatures. The viscosity rating is important because it determines the oil’s temperature operating range. Thin oils with a low viscosity rating flow more easily at low temperatures than heavier, thicker oils with a high viscosity. A low viscosity is good for easy cold weather starting, while a high-viscosity rating helps maintain oil film strength when the engine is hot or when ambient temperatures are high. Viscosity ratings are determined by the American Petroleum Institute using laboratory tests. The viscosity of the oil is measured and given a number, which may also be called the “weight” (thickness) of the oil. The lower the number, the thinner the oil. Viscosity ratings for commonly used motor oils typically range from 0 up to 50. Gear oils typically range from 70 to 120 or higher. A “W” after the number stands for “Winter” grade oil, and represents the oil’s viscosity at zero degrees. Low-viscosity motor oils that flow easily at low temperatures and provide easy cold weather starting typically have a “5W” or “10W” rating. There are also “0W” rated oils for extremely cold climates. Higher viscosity motor oils that are thicker and better suited for high temperature operation typically have an SAE 30, 40 or even 50 grade rating. Most motor oils today are “multi-viscosity” oils (see next question), but single viscosity or “straight” weight oils may be required for some vintage and antique engines. Straight SAE 20 or 30 oil is often specified for small air-cooled engines in lawn mowers, garden tractors and portable generators. Q: What is a “multi-viscosity” motor oil? A: A multi-viscosity or multi-grade motor oil is one that combines the flow characteristics of both a thin and thick oil. This is done with additives and by carefully blending different grades of oils to achieve the desired viscosity range. Multi-viscosity oils have a two number rating. The first number with the “W” refers to the oil’s cold temperature viscosity, while the second number refers to its high temperature viscosity. Popular multi-viscosity grades today include 5W-20, 5W-30, 10W-30, 10W-40 and 20W-50. Most late-model vehicles can use 5W-30 or 10W-30 motor oil for year-round driving, and some may require 5W-20. Always refer to the vehicle owner’s manual for specific oil viscosity recommendations, or markings on the oil filler cap or dipstick. |