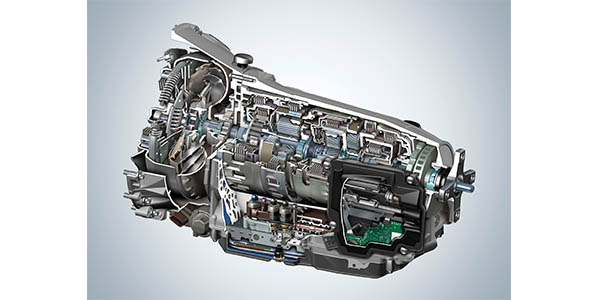

The transmission game has changed. Solenoids, sensors and computers have replaced vacuum lines, governors and kick-down cables on modern automatic transmissions. The tools have also changed: Scan tools, scopes and meters have replaced pressure and vacuum gauges.

Even with codes and datastream information, you must be able to think like the transmission to find the correct diagnosis, which typically doesn’t involve replacing the entire transmission.

Thinking like a transmission means understanding what information the transmission has, how it interprets that information and how it uses the information to select the correct forward gearing. You also have to understand how the transmission prioritizes performance when it is compromised.

Rule 1: The modern transmission is info hungry

On earlier models, once the throttle cable was pulled so far, or a switch under the gas pedal was activated, the transmission would kick down to the next, lower gear.

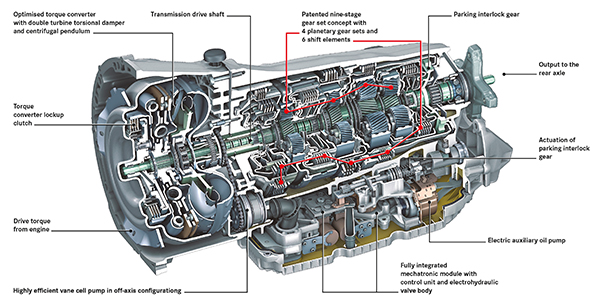

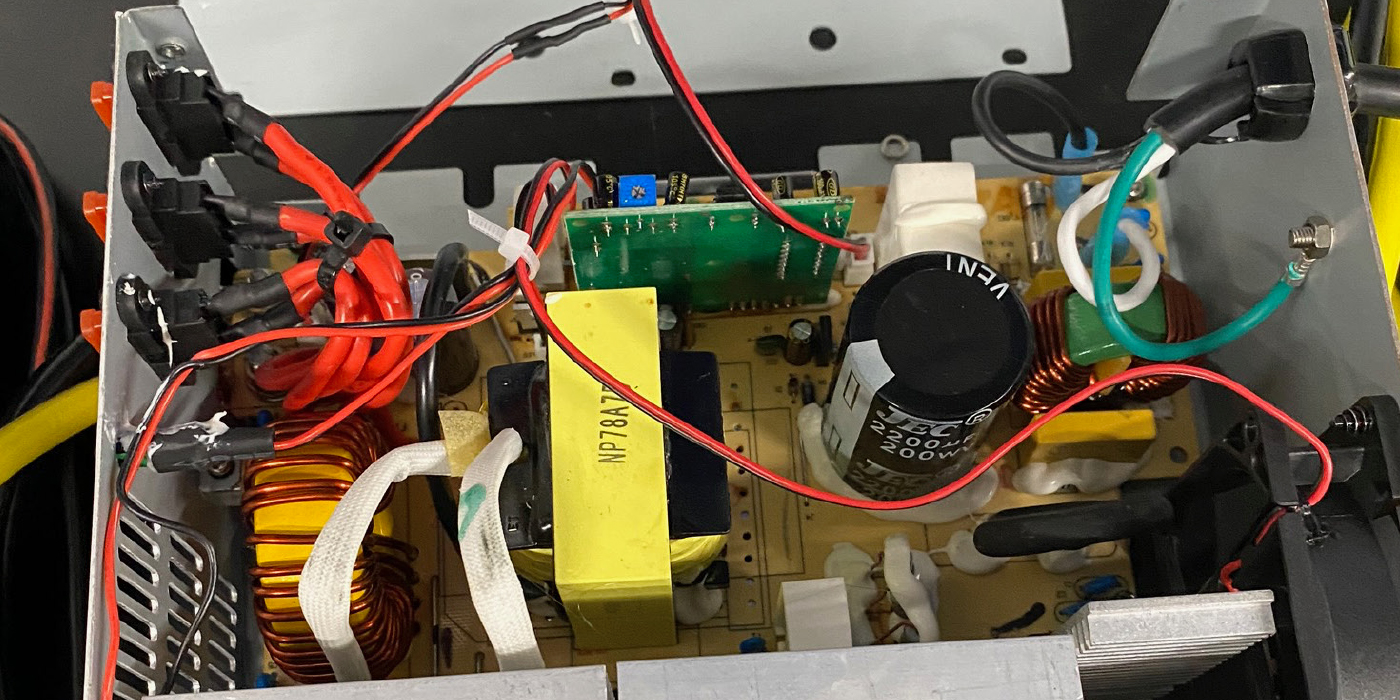

The modern transmission is much more complex. When the driver presses the gas pedal, the request goes to both the engine and transmission control modules. A transmission control module or software may look at 30 different parameters to determine gearing and torque converter settings.

On most late-model vehicles, the transmission is on one of the faster serial data buses, or an exclusive bus that ties it to the engine controller and maybe one other controller. Some use one module to control both the engine and transmission.

The module craves information, and it uses this information to make the best possible shifts — shifts that are efficient, smooth and cause the least possible damage to the wear components inside the transmission.

The control module uses information beyond calculated engine load, throttle position and input/output speeds. Some control modules will look at mass airflow (MAF) sensor and engine temperature information to determine the correct shift points and line pressures.

Relying on this extra information helps the transmission sense additional problems, such as malfunctioning crankshaft position sensors, high engine temperature and even clogged air filters.

If any of this information is missing or outside of operating parameters, the control module will throw up a red flag and set a code. Depending on the discrepancy, the control module might conclude that the problem could damage the transmission and, in turn, reduce power or go into a limp mode as a response.

The engine and the transmission modules tell on each other because they need each other to operate. They will tell a scan tool if they are not communicating. You may find codes for lack of communication between the modules. In the datastream coming from the modules, you may see missing data like MAF sensor’s grams-per-second reading in the transmission module, or a gear selected PID in the engine control module. The fault could be the communication bus that typically is “high-speed CAN” that networks the ABS, Transmission and Engine modules onto their own network.

Rule 2: Transmissions are programmed to save themselves

Instead of letting a transmission destroy itself due to a malfunctioning component, a controller will put the engine and transmission into a safety mode to save the wear components. The driver can’t ignore a limp, failsafe or reduced-power mode.

Customers will notice their speed is limited or their engine is not allowed to rev beyond a preset rpm limit. Internally, the transmission may increase line pressure and change shift points, with some transmissions skipping gears to prevent further damage to the clutch pack.

A multitude of conditions cause a safe mode, including a failure to communicate on a data bus, a failed sensor or a bad shift. The code is just the starting point, not a final diagnosis. Most automatic transmissions will only engage second gear if it detects a problem.

Rule 3: Transmissions adapt to wear; a driver does not

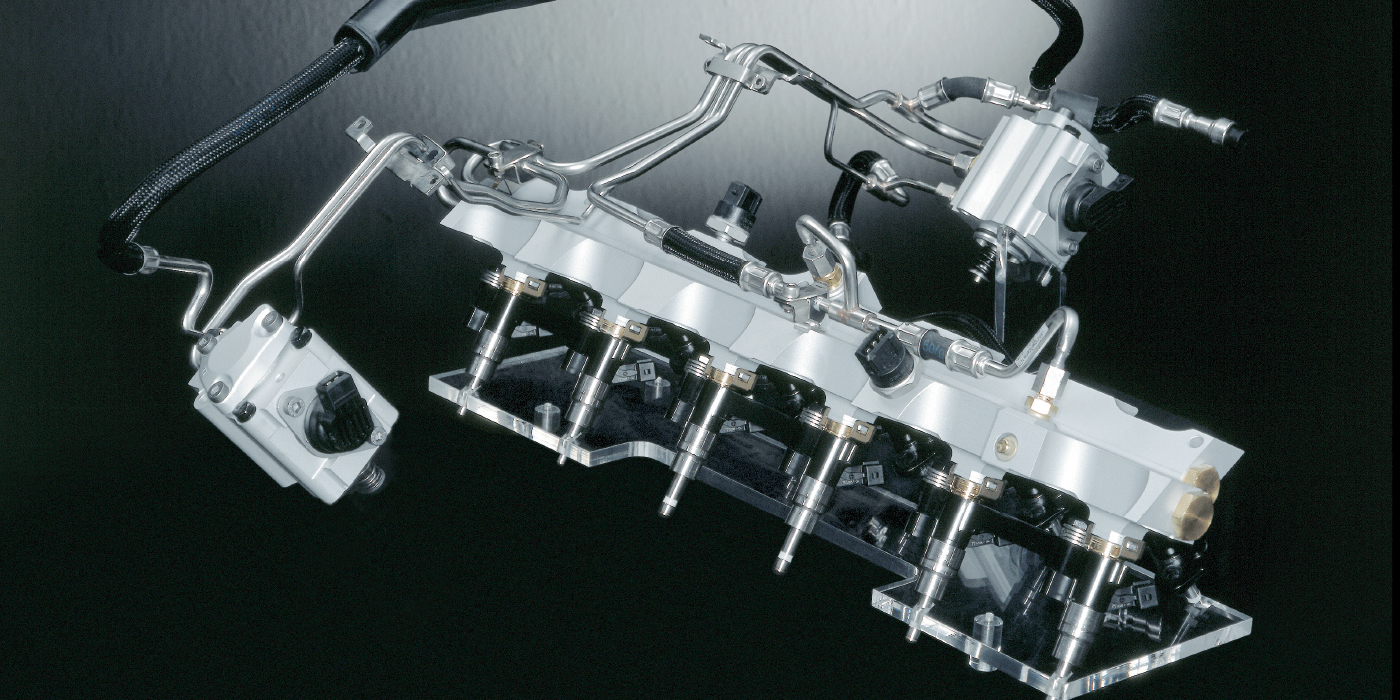

A transmission is programmed to deliver seamless shifting. Having more gears helps, but how those gears are controlled makes the biggest difference. The goal is to engage and disengage clutch packs smoothly, but as a transmission wears, the engagement behavior can change.

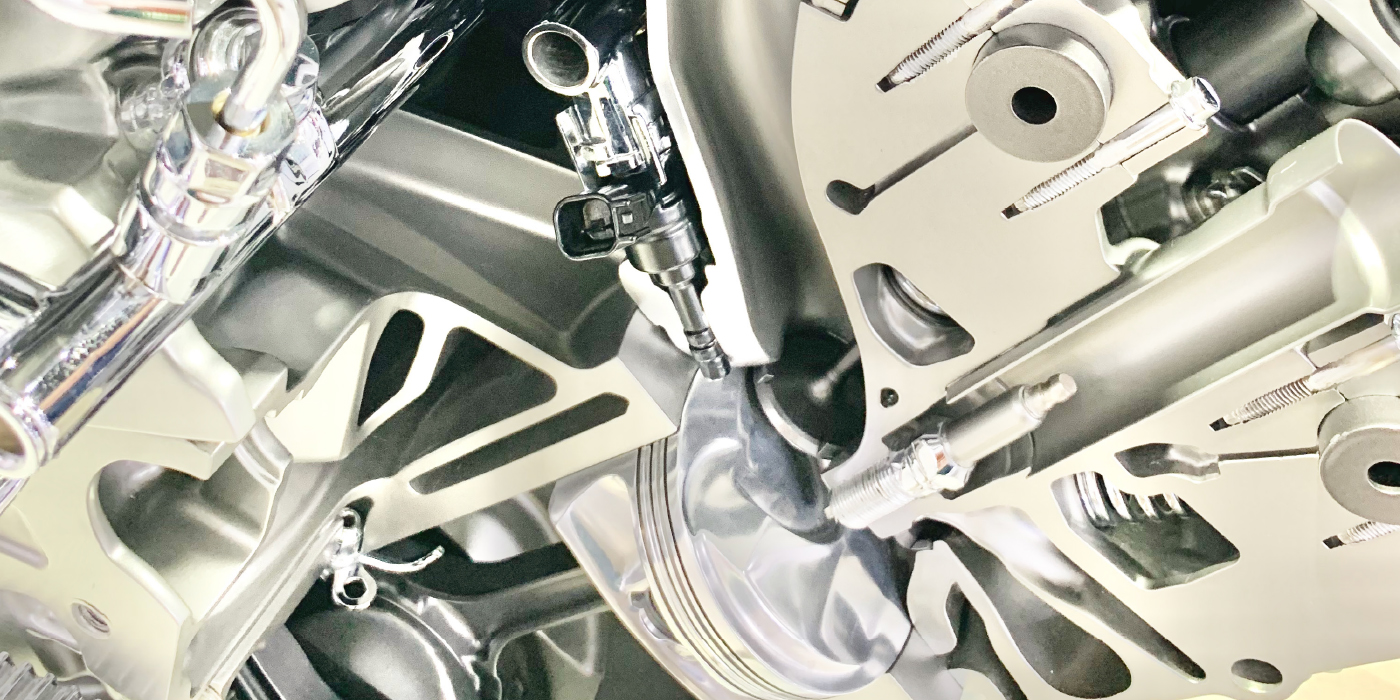

How the transmission determines a shift point is similar to a closed-loop feedback emissions system that still uses short- and long-term fuel trims. When an automatic transmission shifts gears, it looks at the input and output speeds to determine the quality of the shifts.

While changing gears, the transmission may detect a flare in engine rpm that does not produce a change in vehicle speed. The control module will register this as a bad shift and recognize that the clutches are slipping with the current shift program. The control module will then make changes to the shift timing or line pressure in order to eliminate the gap during the shift. This will prevent damage and slipping in the torque converter clutch.

If a clutch is gripping too harshly, the control module may see a sudden drop in rpm with little change in vehicle speed. The control module will then change how the clutches are engaged. Most modern transmissions will set codes if they can’t compensate anymore, or if there is a sudden change in clutch performance.

This adaptation mechanism can also adapt to the condition of the transmission fluid. If the fluid is the wrong specification or has degraded to the point that it’s changing the friction levels of the clutch, the computer will adapt and change the shift behavior.

But, this adaptation feature can mask the problem only for so long, and it can create other problems. For instance, if the module controlling the transmission loses the shift information because the battery was disconnected or the module was replaced, then the transmission will revert to factory settings that do not include the adjustments for clutch wear. So, a minor battery replacement could leave customers accusing you of damaging their transmission.

There are a few methods for recalibrating the transmission control module. You can drive the car or let it run with the wheels off the ground (some ABS/traction control systems won’t allow you to do this), or you could use a scan tool if the calibration protocol calls for it.