Smaller engines, greater diagnostic opportunities.

Turbochargers are not a new technology. In the 1980s and 1990s, many automakers used turbochargers on gasoline engines for performance on limited applications. Many of these vehicles got a bad reputation for reliability and power that came on in one big lump.

By the mid-1990s, many import car and truck manufacturers stopped using turbochargers on their engines. Many replaced turbocharged four-cylinder engines with larger displacement V6 and V8 engines. Why? Automakers had had enough of rising warranty costs, and consumers began to associate turbochargers with trouble.

Twenty-five years later, turbochargers have made a comeback – and it’s been quick. In 2010, only 5 percent of vehicles sold in the U.S. were turbocharged. By 2017, almost 28 percent of cars and trucks sold were turbocharged.

How did they overcome the negative image? First, automakers do not advertise that models are turbocharged in brochures or on the badge on the trunk lid. Instead, they call the engines “Eco” or put a “T” in the engine’s name. Second, they have developed ways to cool the turbo after the engine is shut down to alleviate heat soak. Lastly, they made a turbocharged engine act like a naturally aspirated engine.

Coked Up

Back in the day, It was not uncommon for a turbocharger on some vehicles to last only 30,000 to 40,000 miles. The failures were almost always in the center section and caused by the lack of oil flow to cool and lubricate the bearings and shaft.

The lack of oil was caused by carbon deposits in the lines and passages. The most significant part of the problem were deposits formed when the engine was off, and the turbo was heat soaked.

When an engine stops turning, the oil flowing to the turbocharger stops. The oil inside the turbocharger might drain out of the center section through the return line. The remaining oil in the center section is heated to the point where it is turned to carbon deposits or what some people call “coke.” Carbon deposits can obstruct the passages that carry oil to the turbine shaft and bearings.

When the engine is running, the oil acts as a coolant to draw heat out of the turbocharger. But, for the oil to cool the turbo, it must flow. Restrictions in the oil feed or return lines can cause the turbocharger to operate hotter than usual.

Engine Coolant as Turbo Coolant

Just about every turbocharged engine sold in the past 10 years has an electric pump circulating engine coolant through the turbocharger’s center section for two to five minutes after the engine stops. The circulating coolant helps to cool the turbocharger. Most pumps will free-spin when the engine is running and engage when the engine is off.

Many factors determine the run time and speed of the pump. Most systems look at the engine’s coolant temperature using sensors mounted in the head, block, and radiator. Once a sufficient drop in temperature is measured, the pump will be shut off. Some systems will also look at the previous calculated load and throttle position before the key was removed from the ignition to determine cooling pump run times.

Many engine management systems look at battery voltage to determine how long the pump can run to cool the turbocharger. Most sophisticated systems use the battery life monitor that measures the current draw through the positive battery cable. Most systems will prioritize cranking and starting the engine over cooling the turbocharger in situations where the battery is marginal.

Better Boost

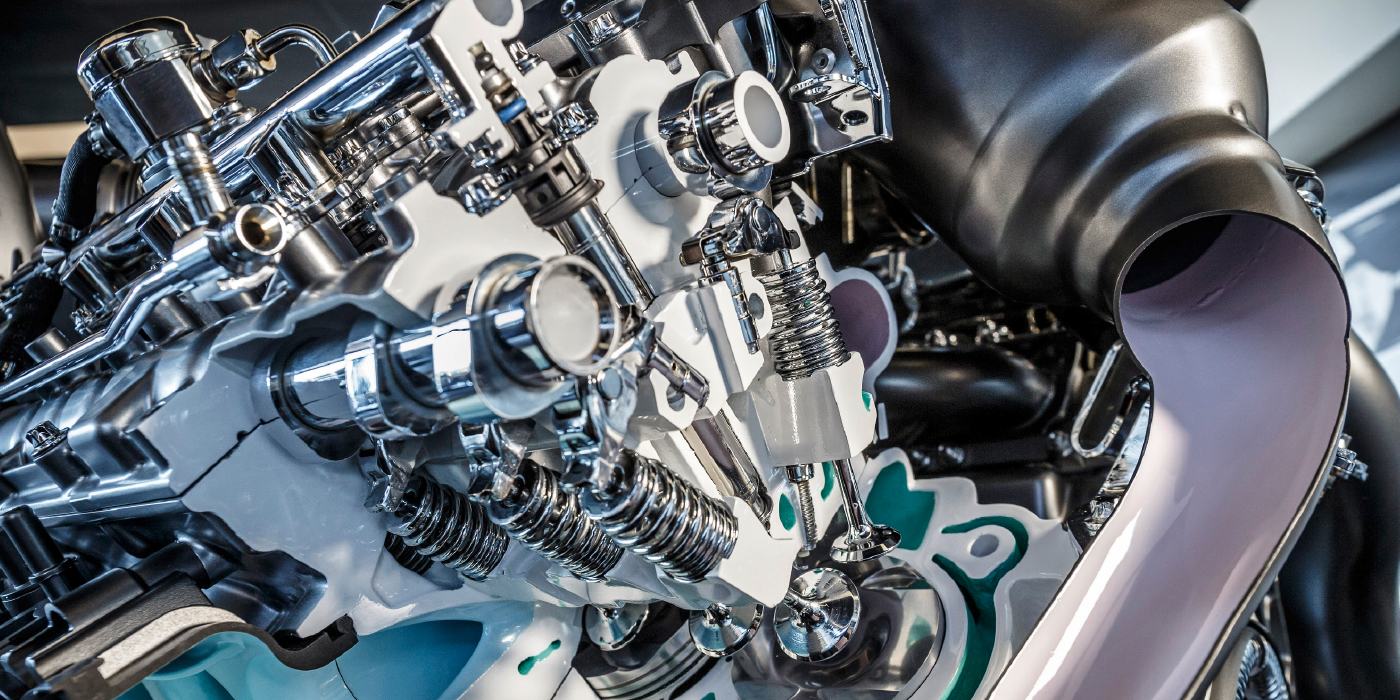

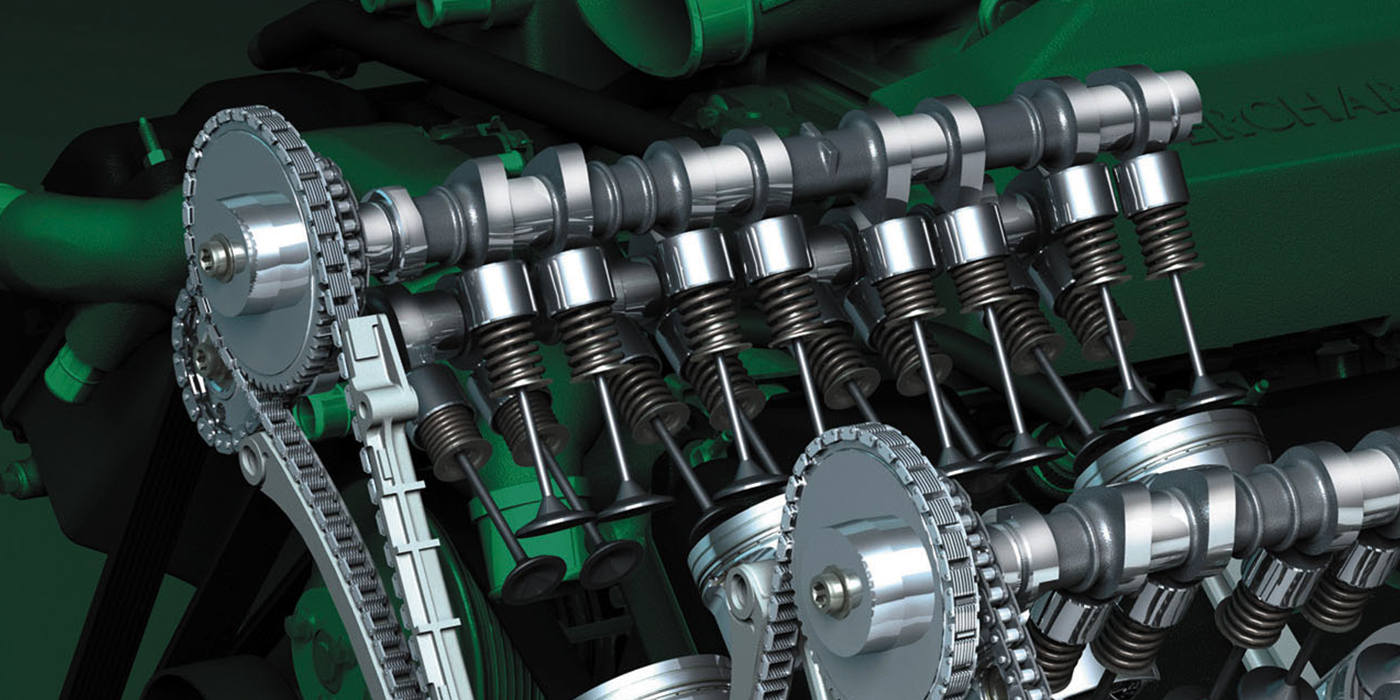

Most vehicle owners don’t know if their car or truck is turbocharged because engineers have created smaller displacement engines that don’t produce much torque in the lower rpm ranges. With better engine management systems, variable valve timing and electrically operated wastegates and bypass valves, the engine can have the same powerband as an engine twice its size.

Most modern turbochargers use an internal bypass valve that recycles the excess boost into the intake system before the compressor. The bypass valve is an electronic motor on most modern turbochargers, rather than a spring and diaphragm calibrated to a maximum boost pressure. Some vehicles and scan tools will allow you to actuate the bypass valve. You can also watch the live datastream on a test drive to see how the valve is used to manage the speed of the compressor or exhaust turbine wheel. The bypass valve prevents the surging of the air when the throttle valve is shut. The surge of air can stall the compressor wheel and cause stress on the shaft.

The wastegate on the exhaust side of the turbocharger regulates the speed of the exhaust turbine. When the wastegate opens, it routes exhaust gases around the spinning turbine to the exhaust manifold or downpipe. This causes the turbine to slow down and boost to be reduced. If the valve is stuck open, the turbine will not spool up, and the boost will not be generated. If the valve is stuck shut, there can be rapid changes in compressor speed.

If the turbocharger is a dual-scroll design, the turbocharger’s exhaust side might have a valve between the exhaust manifold and turbocharger. The valve directs the exhaust gases over different parts of the exhaust turbine. The valve is used to control the speed of the turbocharger and boost levels.

With all three valves working together, the boost can be kept in a range where the best fuel economy and power can be produced from a smaller engine. This can be done below 3,000 rpm.

Diagnostic Hints

One of the most common problems with turbocharged vehicles happens with customers who use the wrong oil. The oil that is certified by an OEM for its turbocharged engines is used because it can handle the heat. NOACK testing is performed by heating the oil to 250˚C for one hour under a constant flow of air. The oil is weighed before and after the test. When oil evaporates, it leaves behind carbon and sludge that can damage the turbo and engine. The lower the NOACK number means less oil has evaporated. Also, some manufacturers might give a “flashpoint” temperature for the oil. This number is the temperature at which the oil evaporates when exposed to heat. For turbocharged engines, a higher flash point means it will not break down when pumped through the hot center section.

The most common restriction for turbochargers are not blockages in the feed line, but elevated crankcase pressure that restricts the return line. The return line on most engines is plumbed into or above the oil pan. If crankcase pressures are high due to blowby or a restricted PCV system, the oil coming from the turbocharger will have to overcome the pressure to drain into the oil pan.

Making sure the engine has the latest ECU calibration is key to allowing a replacement turbocharger to survive. The latest calibration can enable the turbocharger to cool in less time, reducing the likelihood of the oil coking in the oil feed pipe.

Diagnosing an under-boost condition on a modern engine requires a scan tool to graph multiple data PIDs from the datastream. The two most important parameters to look at are the desired boost pressure and the actual boost pressure during a test drive.

The first thing to notice is if the boost reaches the desired level. If the boost is low, it is a sign there might be a leak in the system. If the boost is slow to build, it could be a sign there might be an issue with the wastegate or bypass leaking.

The next parameter in the datastream is to look at the position or duty cycle or requested position of the bypass or wastegate valve compared to the boost pressure. If boost pressure does not change, it could indicate a mechanical issue. If there no change, it could indicate a mechanical issue.

It is estimated this year, 50% or more of vehicles sold in the U.S. will have one or more turbochargers under the hood. There are already significant numbers of vehicles on the roads that are turbocharged and need service. Some of the fixes do not involve replacing the turbocharger, but the support components that keep it healthy.