A lot of engine specialists who sell crate engines, as well as custom engines, promote “street/strip” engine packages. The implication here is that such engines will run well on the street and still be competitive on the drag strip. These engines are typically rated anywhere from 450 hp up to 650 hp for small blocks, and up to 800 hp for big blocks running pump gas.

A lot of engine specialists who sell crate engines, as well as custom engines, promote “street/strip” engine packages. The implication here is that such engines will run well on the street and still be competitive on the drag strip. These engines are typically rated anywhere from 450 hp up to 650 hp for small blocks, and up to 800 hp for big blocks running pump gas.

We have all seen in our industry that a “streetable” racing engine or a “raceable” street engine appeals to a broad spectrum of potential engine buyers because of its flexibility. Yet, everyday street driving is not the same thing as serious drag racing.

Street performance engines are all about driveability, throttle response and low- to mid-range torque. Drag engines, on the other hand, are all about brief bursts of power, acceleration and pushing a vehicle from the starting line to the finish line in the least amount of time.

The trick is to build an engine that can satisfy both sets of requirements without making too many compromises. The street/strip engine that results should be one that starts easily, idles reasonably well and can be driven normally around town, yet delivers serious go-power when the pedal is to the metal.

Fueling Considerations

Fueling Considerations

Building a street/strip carbureted engine is more challenging than building a fuel injected street/strip engine because of the fixed jetting, choke and accelerator pump in the carburetor. A street engine needs a certain amount of intake vacuum to pull fuel through the carburetor.

For good throttle response, you can’t go too big on the cfm (cubic feet per minute) rating of the carburetor. A 600 cfm is probably the best choice for a street driven small block engine, and a 750 cfm for a big block motor. For starting and cold driveability, you have to retain the choke on a street engine.

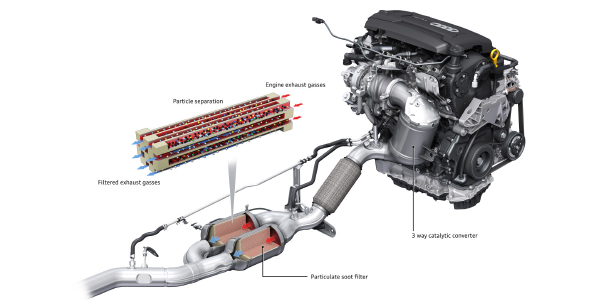

And for emissions, you have to retain the PCV and EGR vacuum hookups. You also can’t go too rich on the jetting for a street carb otherwise you’ll kill the fuel economy — and also create emissions problems for your customer if the vehicle ever has to be smog checked.

With electronic fuel injection (EFI), the fuel system is more adaptable because fuel metering is handled electronically by the powertrain control module (PCM). Cold starting and cold driveability are much better than with a carburetor, and there is no troublesome choke, accelerator pump or power valve to cause driveability problems.

The EFI system relies on various sensor inputs to modify the air/fuel ratio, so the throttle position, airflow and oxygen sensor inputs are important. Tuning a modified fuel injected engine, therefore, usually requires recalibrating the computer with a new PROM chip or flash reprogramming the EEPROM.

And if a modified street/strip engine puts out significantly more power than stock, oversized fuel injectors are usually required.

If all you’re doing is machining and assembling the engine itself (the long block) and you are not building a complete turn-key engine or doing the final dyno tuning, then installing and tuning the fuel and ignition systems is normally your customer’s responsibility, not yours. Even so, the engine you are building has to be purpose-built for how your customer will ultimately use it.

If he wants a killer drag motor, build him a killer drag motor. If he wants a stocker with some extra punch, you can do that as well. And, if he wants you to build him a street/strip engine that hopefully will do both, you better find out exactly what he expects, what kind of vehicle the engine will be going into, and how that vehicle will ultimately be driven. A lot of street/strip engines are never raced at a drag strip. They’re really street racers that serve double-duty as a daily driver or a Saturday night cruiser.

Drag or Street Engine?

Drag or Street Engine?

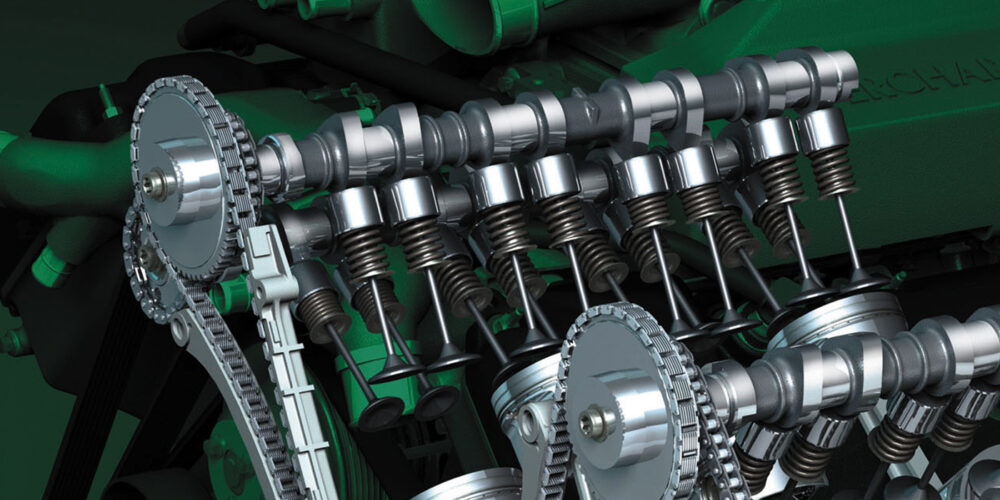

Pro Stock drag racing engines are the ultimate in carbureted engine performance today. Most of these engines are monsters, displacing 600 to 800 cubic inches. They use long stroker cranks, aftermarket blocks with larger bores and bore spacing, and highly massaged CNC ported aftermarket cylinder heads with gigantic ports and valves.

These engines are running radical profile roller cams, high lift roller rocker arms, oversized pushrods and extremely stiff valve springs, so they can rev to 9,500 rpm or higher. They have ram style manifolds with mega-cfm carburetors that can flow gobs of air at high rpm.

The power curves on most of these engines start at 4,500 to 5,500 rpm and goes up from there. These are purpose-built race engines that are not streetable by any stretch of the imagination.

Everything that goes into one of these engines is designed to maximize airflow so the engine will produce high rpm power. The camshafts have lots of lift and duration, the valves and valve ports are huge to flow lots of air, compression ratios are high to get the most bang out of the fuel (which is high octane race gas), piston rings are often gas pressurized to improve sealing under high loads, and pistons, rods and crankshafts are all forgings to handle the extreme loads.

Pro Stock engines are also built for short runs rather than sustained or endurance racing. That means frequent maintenance. Valve springs are replaced on a regular basis. If the engine has aluminum rods, the rods are replaced after so many runs.

By comparison, the typical street engine operates in an entirely different environment. It spends much of its time idling and running at low rpm and low load. Throttle response is essential, and most street engines have a broad, flat torque curve that develops peak power from 1,500 to 4,500 rpm.

Fuel economy is important, and so is durability. Nobody wants to replace valve springs, rods or other parts on a street engine. They expect these parts to last year after year, just like a stock engine.

The ideal street engine, therefore, is one that delivers a broad torque curve and pulls strong from idle through mid-range and beyond. It doesn’t require super stiff valve springs and oversized pushrods because it doesn’t have to rev much higher than a stock engine.

It doesn’t need cylinder heads with huge ports and valves because it needs to keep air velocity high for good throttle response and low rpm torque. It doesn’t need a lot of carburetion because it’s not a high revving engine. And, it shouldn’t need a lot of expensive race-quality internal parts because it’s not really a racing engine. It’s a street performance engine.

Stroker motors are popular because they add extra cubic inches and torque without changing much else. You do have to compensate somewhat for the extra cubic inches when it comes to sizing the head ports and choosing a camshaft and intake manifold.

A larger displacement engine can handle larger head ports, and a longer duration cam, but you need to choose a cam that’s designed to work with the higher piston velocities in a stroker motor.

As for big block or small block, bigger is almost always better for a street/strip engine — as long as the engine will physically fit into the vehicle. More cubic inches is more power and torque at all speeds. If fit is an issue, some of today’s stroker kits can stretch a small block to big block proportions. A 383 stroker kit is a nice upgrade for a 350 SB Chevy, but a 427 stroker kit is even better.

Selecting the Cam

The lift, duration and overlap of the camshaft will determine the engine’s torque and power characteristics, so choose carefully to get the best combination that matches how the engine will actually be used. A street/strip engine will perform best with a good mid-range cam that has higher lift than stock but not too much valve overlap or duration.

Stock and slightly modified engines typically perform best with a camshaft that has 270-290° of duration (SAE). Such a cam will deliver good idle quality and low rpm torque. The next step up would be a cam in the 290-300° range. Such a cam will give fair idle quality and deliver good low to mid-range torque. A cam with 300-320° will idle rough and deliver power from mid-range to high rpm.

Longer duration cams work best with manual transmissions or a high stall speed torque converter if the vehicle has an automatic transmission. A lower final drive gear ratio may also be required to get the engine into its optimum power range. Higher gear ratios are great for acceleration off the line, but they also kill fuel economy on the highway unless the transmission has overdrive gears to compensate. Any cam over 320° duration is usually a race-only cam and should not be used on the street.

A strong street engine should also be running a roller cam rather than a less expensive flat tappet cam. A roller cam reduces friction and allows a steeper cam lobe ramp profile to open and close the valves more rapidly. Hydraulic lifters are the best choice for a street/strip engine because they are quieter than solid lifters, and they eliminate the need for frequent valve lash adjustments.

Forged aluminum or steel high-lift roller rockers are a nice addition on any engine, but you can often get by with stamped steel rockers on the street because the valve spring pressures are not much higher than stock. Standard-sized chrome moly pushrods should also be adequate for a street engine that seldom sees the high side of 5,500 rpm and does not have to withstand more than a couple hundred pounds of open valve spring pressure.

Around the Block

Around the Block

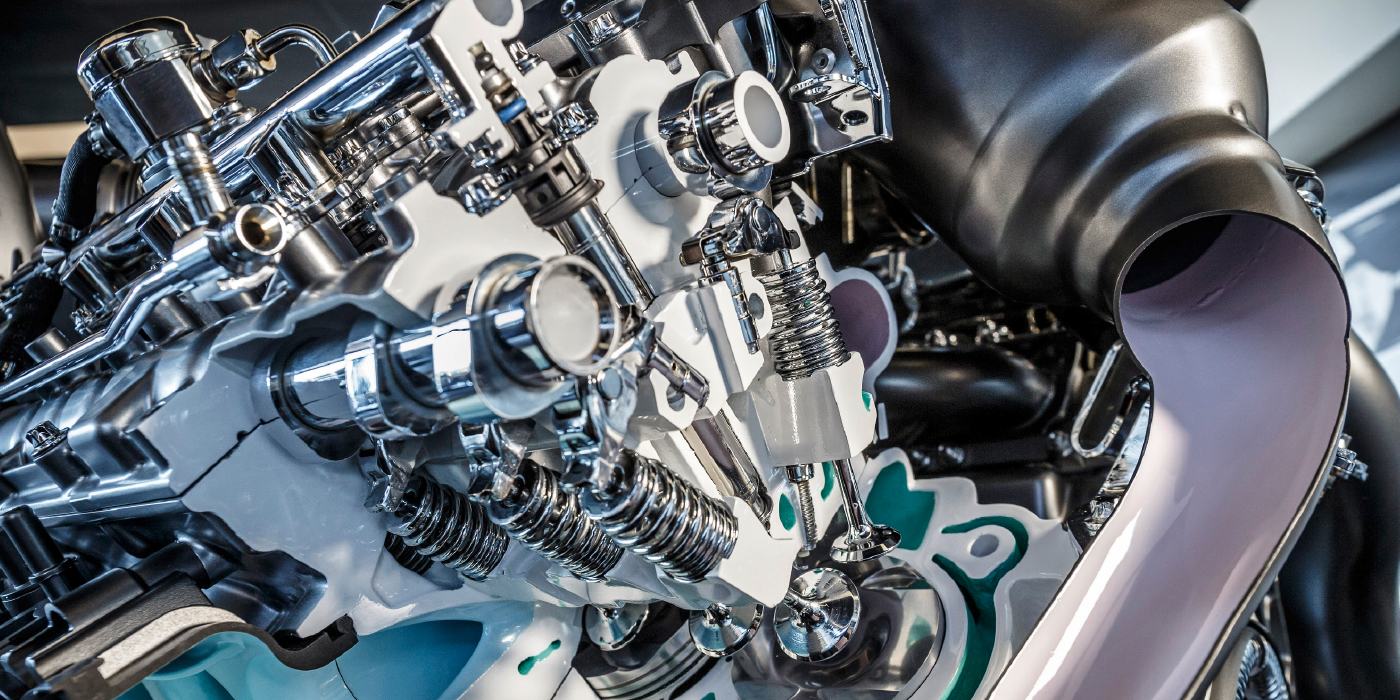

Most stock blocks are more than adequate for a street/strip engine. But, if cost is not an issue, an aftermarket block can add strength advantages and additional displacement. Likewise, stock cylinder heads with mild porting can deliver good power in a dual-purpose street/strip engine. But for serious power gains, upgrading to aftermarket bolt-on street performance heads is one of the best modifications you can make.

There are many heads to choose from, with various valve angles, valve sizes, port sizes and combustion chamber styles. Avoid the temptation to go with a race head because the ports are usually too large to produce low rpm torque and throttle response.

An aftermarket street performance head for a small block engine should have intake ports in the 165 to 205 cc range, around 290 cc’s for big block oval port heads, and up to 315 cc for big block rectangular port heads. The larger the ports, the more air they can flow. But larger ports also move the engine’s power band further up the rpm scale. If the ports are too large on a street engine, the engine will have poor throttle response and poor low-end torque.

Many of these aftermarket street performance heads will mate with stock or aftermarket intake and exhaust manifolds, which helps keep the cost down. The next step up would be matched cylinder heads and manifolds. The advantage here is more flexibility in port location, height and configuration.

As for valves, you don’t really need anything that’s very exotic. Lightweight titanium valves are great in a high revving race engine, but for the street they are overkill. You don’t need the weight savings or the expense. A good set of stainless steel valves will do fine.

The valve seats should have a multi-angle valve job to optimize flow and velocity. Generally speaking, the more angles there are on the seats, the better the seat flows. A stock valve seat with only a single 45° angle cut on it will have a sharp edge just above and below the area where the valve sits on the seat.

As the valve starts to open and air begins to flow past the valve, the abrupt change in angles creates turbulence that reduces air velocity and flow. It can also cause the air/fuel mixture to separate. So cutting another angle above the primary seat and a third angle below the seat helps smooth out the air flow.

That’s why a traditional 30-45-60° three-angle valve job produces more power than a stock valve job. Better yet is a four-angle valve job with a fairly steep top angle that allows for a better transition from the seat into the combustion chamber. A 37° top cut with a 45° seat, a 58° undercut below the primary seat, and a 70° cut below that will flow better and make more power than a three-angle seat.

As for the compression ratio in a street/strip engine, keep in mind the limited octane rating of most pump gas. If you keep the static compression ratio less than 10:1, detonation should not be a concern with 91 octane premium fuel. Some engines, like Chevy LS1 through LS7 engines, can safely handle higher compression ratios up to 11.5:1 on pump gas due to the shape of the combustion chamber.

If an engine has electronic fuel injection and a knock sensor, you can often get away with higher compression ratios because the knock sensor will retard spark timing if the engine starts to detonate. But with a carburetor and no knock sensor, too much compression is risky.

Forged pistons and low tension steel or ductile iron rings are good in any motor, but a street/strip engine can also run less expensive hypereutectic pistons up to about 450 hp to 500 hp. Flat top pistons are usually better from a combustion standpoint than pop-up pistons. And with a low revving engine, you don’t need huge valve reliefs in the piston domes. An anti-friction coating on the piston skirts is good insurance against scuffing.

Opinions are mixed about the suitability of aluminum rods for street engines, but with so many H-Beam and I-Beam forged steel rods to choose from, why bother? For a street/strip engine, you want strength and durability.

A street/strip engine also needs a good crankshaft. Cast cranks can handle up to 400 hp, but beyond that a forged steel crank is best. There’s no need to go to the expense of installing a high revving lightweight racing crank. The crank should be balanced along with the rest of the reciprocating parts for smoothness and durability, but balance isn’t as critical as in a high revving race engine. Balance within 4 grams (0.14 oz.) is a good benchmark for a street engine, while 2 grams (0.07 oz.) or less is the norm for a racing engine.

Matching Up Manifolds

The intake manifold for a street/strip engine needs to be one that keeps air velocity high and flows best in a low to mid-range. That usually means a 180° dual or split-plenum style manifold under a carburetor rather than a 360° open or single-plenum style manifold.

A high rise manifold with longer runners is also better than a low rise manifold as it improves air velocity into the cylinder heads. On a fuel-injected engine, longer intake runners are best for low to mid-range torque. If the engine has to be emissions legal, the manifold will also require an EGR port.

Boosting Power

Forced induction is a great way to add power to any street/strip engine. Turn up the boost pressure and you turn up the power. Superchargers typically deliver more low end boost and better throttle response than turbochargers, which take time to spool up and develop boost pressure.

Most turbos don’t do much below 3,000 rpm. If you are building an engine that will be boosted, you may have to reduce the compression ratio down to 8:1 or 8.5:1 to reduce the risk of detonation.

Nitrous oxide is another power booster that can add punch in a street/strip engine only when it’s needed. NOx causes combustion temperatures and loads to soar, so the bottom end of the engine block has to be stout enough to handle the extra load. Four bolt main caps, a forged crank and rods are recommended.

Exhaust headers can also enhance engine breathing, but for a street/strip engine you want shorter length, smaller diameter tubes that keep exhaust velocity high for good flow, throttle response and low end torque. Larger diameter, long tube headers are great for making high end power, but can be counterproductive on the street. Thermal barrier ceramic-metallic coatings on the headers will keep heat in the exhaust and improve exhaust gas velocity.

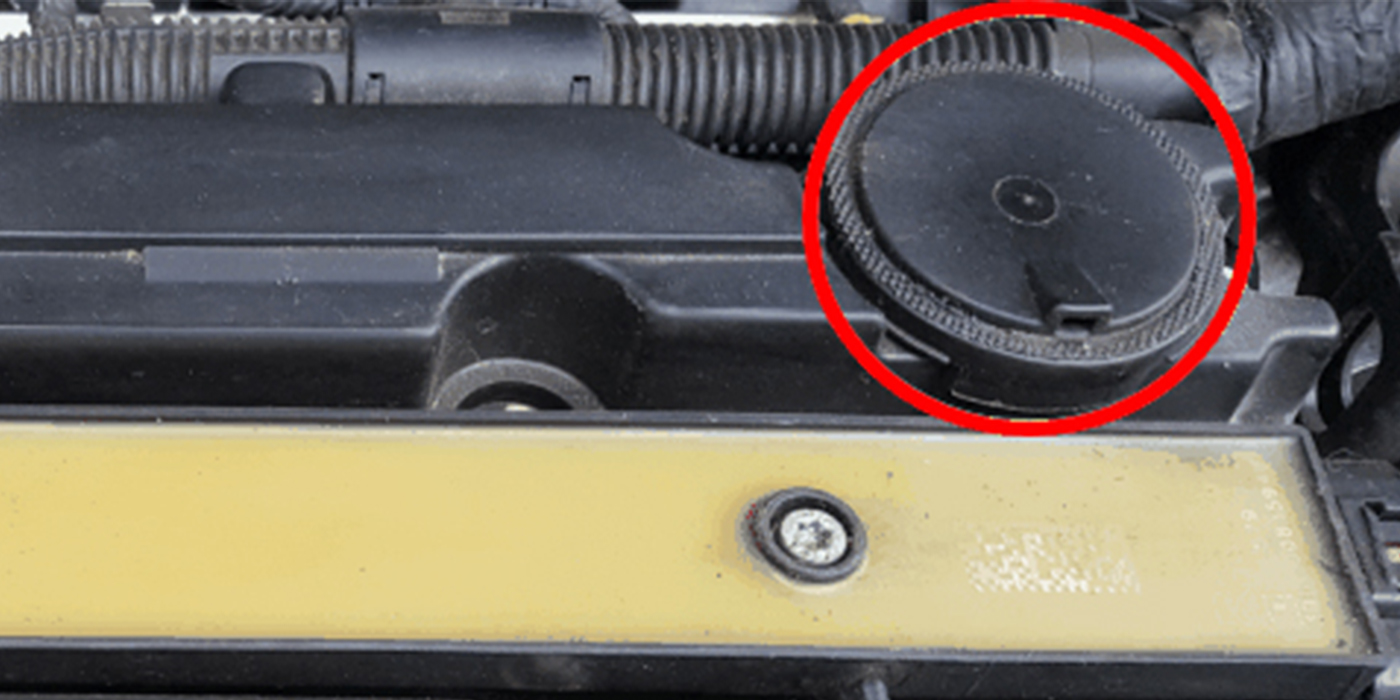

Other add-ons that are needed with a street/strip engine include a stronger clutch or a stronger automatic transmission (with an auxiliary ATF oil cooler), and a good cooling system (possibly a larger capacity radiator and larger or extra cooling fan).

As for engine lubrication, you don’t need a dry sump oiling system for most of these engines. A good aftermarket high volume oil pump should keep the oil flowing. Most engines only need about 10 psi of oil pressure for every 1,000 rpm of engine speed.

A larger capacity oil pan is a plus, with six to eight quarts being more than enough for most engines. As for oil, recommend a 5W-30 rather than a 15W-40 racing oil. The thinner oil will flow better at cold temperature and improve fuel economy.