What is a “Misfire?”

What is a “Misfire?”

A misfire, also commonly referred to as a “skip,” is simply the lack of engine combustion. When it came time for a cylinder to fire, it simply missed its chance to do so from either a lack of spark, fuel, air or compression.

Generally, when a customer brings a vehicle into a shop that has a misfire concern, they will describe it as “bucking,” “jerking” or loss of power. They also may describe it, depending on the cause, as a jerking when they take off from a start, but smoothes out once the vehicle gets moving. They may tell you the check engine light has been flashing.

There are two main types of misfires: a type “A” and a type “B.” The PCM tracks misfires and calculates the percentage of them two ways: over a 200-rpm range and a 1,000-rpm range.

If too high of a percentage of misfires occur over a 200-rpm period, they are counted as type “A” misfires. If a high enough percentage of these occur, the PCM sets a fault code and flashes the check engine light to get the driver’s attention.

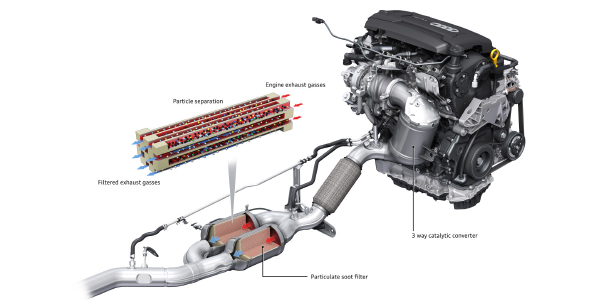

Type “A” misfires are damaging to a catalytic converter. To help protect the converter, many vehicles will shut down the injector to the offending cylinder.

Type “A” misfires are damaging to a catalytic converter. To help protect the converter, many vehicles will shut down the injector to the offending cylinder.

Misfires that occur outside that 200-rpm period, yet occur within a 1,000-rpm period are logged as type “B.”

If a high enough percentage of misfires occur within a 1,000-rpm period, the PCM will set a pending code with no check engine light. If they occur again within another 1,000-rpm period, the PCM will set a fault code and illuminate the check engine light without flashing it.

Type “B” misfires are not considered to be catalyst damaging. However, they can be tricky to find on some vehicles because they may happen too intermittently to set a code.

To add to a type “B” misfire’s illusiveness is the fact that on some vehicles an engine may be allowed to misfire as much as 3% of the time over a 1,000-rpm period before being counted in the code-setting criteria. Depending on when a vehicle like this misfires, it may never set a helpful code.

To add to a type “B” misfire’s illusiveness is the fact that on some vehicles an engine may be allowed to misfire as much as 3% of the time over a 1,000-rpm period before being counted in the code-setting criteria. Depending on when a vehicle like this misfires, it may never set a helpful code.

Diagnosing the cause of a misfire begins like any other complaint. The first step is to verify the symptoms, so I take the vehicle out for an initial test drive. This test drive may vary in length from as long as several miles to as short as the parking lot to the service bay, depending on how frequent the problem is. But the key here is, I want to feel it from the driver’s seat. And I want to be armed and ready, so I bring my scan tool with me.

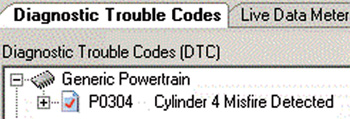

First, key on and engine off pulling fault codes from all modules. The newer the vehicle is, the more critical coding all the modules becomes. When retrieving misfire fault codes from a vehicle’s PCM, be sure to pay particular attention to any non-misfire related codes such as ones that are rich, lean or fuel pressure related. These can be clues as to why the engine misfired.

In the case of a lean code however, it should be taken with a grain of salt. In the textbook order of things, a misfire code will not set before a lean code because the misfire monitor must pass before the O2 monitor will run. However, in the real world with all of the different combinations of driving and possible causes, occasionally a lean code may be set by a misfire.

Getting a Clue

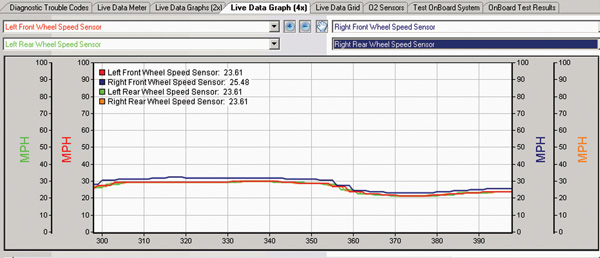

Wheel speed sensor codes can be a clue that the misfire is induced by the traction control. Communications fault codes can be a clue to a faulty ignition coil spiking the PCM. Codes that point to missing data from the PCM such as engine coolant temp or rpm and vehicle speed codes in modules like the instrument cluster are also clues to a faulty ignition coil.

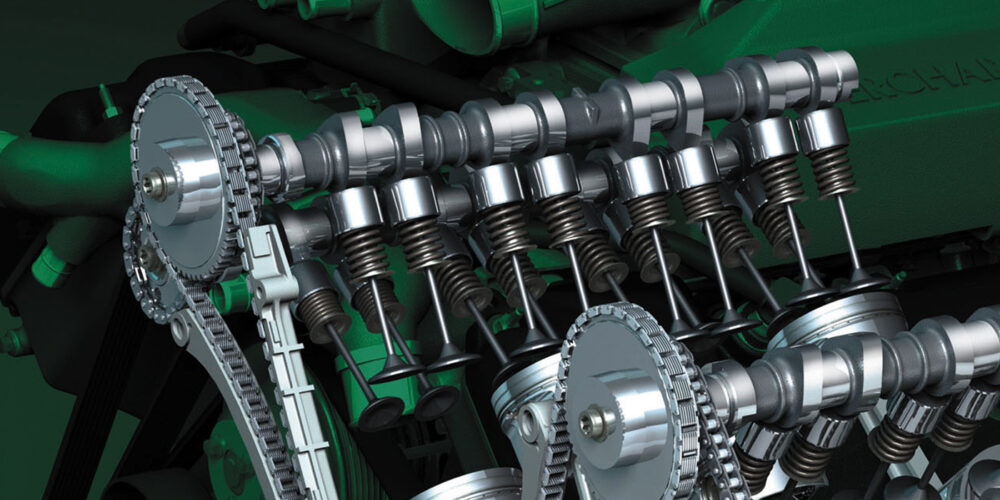

Cam degree error codes are a clue of faulty cam timing, while a rich condition on one bank with a lean condition on the opposite bank can be a clue to a restricted catalytic converter. Injector and coil circuit codes are just plain obvious.

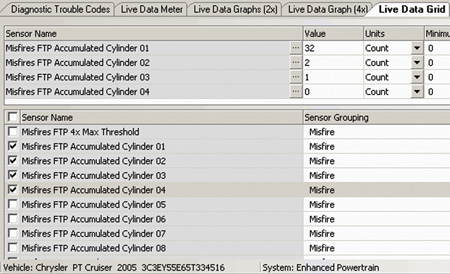

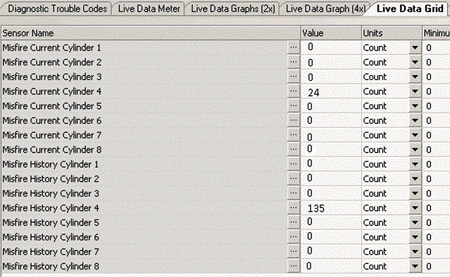

With or without the presence of fault codes, I want to next utilize misfire history PIDs in the PCM where available. Vehicles like GM and Chrysler may display them right along with other engine data PIDs. Ford will display it in mode $06.

Some vehicles may not offer a history at all. I note any cylinders that are displaying a history of misfires.

Some vehicles may not offer a history at all. I note any cylinders that are displaying a history of misfires.

Before starting the engine, I check the oil and the coolant; let’s make sure there is some in it and there is not something obvious here like water in the oil and oil in the water.

Give it a Crank

Now it’s time to start the engine. Let’s give it a listen for obvious engine noises that could be a broken valve spring or other menacing sounds that make one wish they hadn’t forgotten their cell phone back in their tool box. This is also a great time to look over the engine harness. Or rather, what can be seen of it.

This is not an intrusive check at this point, just look for anything obvious like wiring on the exhaust, or chewed wires. I often also walk around the back and listen to the rhythm of the exhaust.

If nothing is obvious, then it is time for a drive. I want to utilize any live misfire data PIDs available. For some vehicles, an OE-level scanner may be needed for live misfire counting. During an engine misfire while driving, I want to watch for unusual instrument activity.

A jumping temperature gauge, tachometer, speedometer, flickering theft light, ABS light or SRS light (as well as others) can all be clues to a faulty ignition coil. I also want to note the behavior of the misfire. If it does it only when accelerating, it is very likely that a secondary ignition component is breaking down. If it only does it at idle, then cam timing, vacuum leaks and EGR leakage become more suspect.

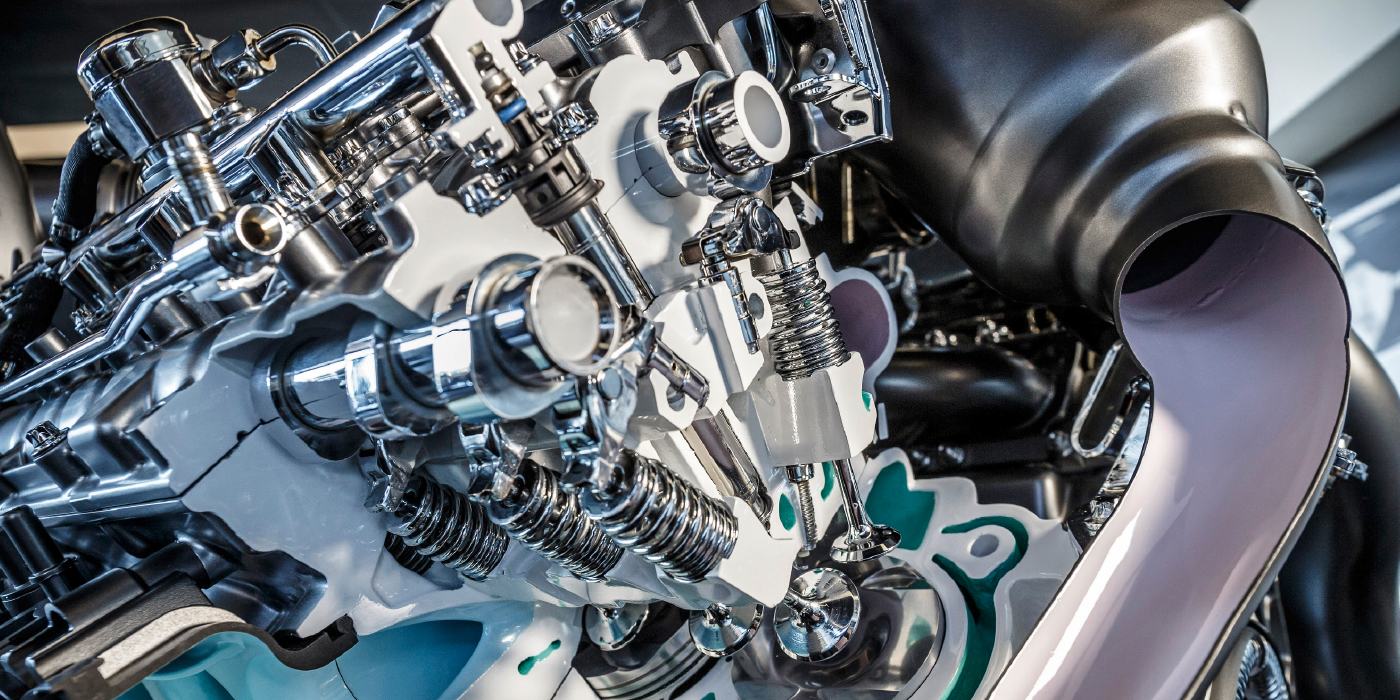

Though there are many possible causes for a misfire, probably the most common types are ignition-related misfires, particularly on the secondary side. There are many types of ignition systems on the road today. We still see some of the old distributor types running around, but most are some form of distributor-less ignition. The basics are pretty much the same regardless. A 12-volt feed is supplied to one side of the ignition coil, while the other side is triggered by either the PCM or ignition module.

For a “blast from the past,” — yes they are still out there — there are even mechanical contact points. To understand the basics of how today’s complex systems work, all we need to do is look at their ancestors, the point ignition. The points were nothing more than a switch on the ground side of the coil.

The points (switch) would close, allowing the 12-volt current supply to flow through the winding of the coil. This would build a magnetic field inside the coil within the windings around an iron core. When the points would open, the magnetic field would collapse and induce a high voltage into the coil. With only one place to go to find ground, the high voltage would flow through the wires and to the plug via the distributor cap and rotor, which would be lined up with the correct cylinder at that time.

That same thing…well basically…happens in the most complex of ignition systems today. Only the “switch” is a transistor located in the PCM (or in an ignition module on systems newer than points, but older than today’s machines). Anywhere that the high voltage, ranging from around 10 kV at idle to around 25 kV under hard acceleration, can find a path that is not the spark plug’s tip will cause a misfire.

This can be a path down the outside of the spark plug, out the side of a plug wire or within the coil itself. One of my favored quick and low-tech methods of finding a faulty ignition coil is to simply stress the coil. I want to see where the coil’s peak output is.

A good coil should be able to peak at around 35 kV. That is about an inch and a half ambient air gap when coming straight out of the coil to engine ground.

Not being colorblind here also helps, as the spark at those voltages should be enough to heat the air to a nice blue flash.

Occasionally, a faulty coil will pass this low-tech testing method and may require an oscilloscope to find.

When testing the low-voltage side of a faulty coil, a negative spike or “tail” present at the point of discharge is often the clincher. The proper term to this charge time is “dwell.”

The term dwell is rooted in the old point-style ignition referring to the amount of time the points were staying (or dwelling) in the closed position. Back then, dwell was mechanically set by an air gap that was rough-set using a feeler gauge, and fine-tuned using a dwell meter. Today, that is electronically controlled.

Other key points to look for are a shortened charge time. If the charge time is too short, the PCM may be limiting its dwell due to a shorted primary winding.

Arching from plug wires can often be found with a squirt bottle of water or a true-bulb test light with the lead grounded and simply passing the metal probe over the wire and boot, looking and listening for an arch.

Often when a spark plug has been flashing over, the evidence can be seen as a black trail down the porcelain of the plug and inside the plug wire’s or coil’s rubber boot. If either is found, both mating pieces must be replaced at the same time or the old trail left in the old part will create a vicious cycle of repeat misfires and failed new parts.

The engine’s fuel system is another popular cause of misfires. A fuel mixture that is either too rich or too lean can cause a misfire. A fuel injector will typically cause a single engine misfire of multi-point injection systems.

Whereas, a malfunctioning fuel pump, vacuum leak, EVAP system excessive purge, un-metered air leak, improper use of E85 fuel, leaking EGR valve, MAF sensor or MAP sensor will usually cause a multiple cylinder (or random) misfire. On the older center-point injection systems, the injector is still suspect for multiple cylinder misfires.

Whereas, a malfunctioning fuel pump, vacuum leak, EVAP system excessive purge, un-metered air leak, improper use of E85 fuel, leaking EGR valve, MAF sensor or MAP sensor will usually cause a multiple cylinder (or random) misfire. On the older center-point injection systems, the injector is still suspect for multiple cylinder misfires.

Usually, but not always, a fuel-induced misfire will be accompanied by lean or rich fault codes. Looking at the fuel trims in the misfire freeze frame can be helpful in spotting this. Trims that are plus or minus in the teens are clues that a misfire has been caused by a lean or rich mixture.

When testing for E85, take a fuel sample. Does it smell weak of fuel? Is it unusually clear? Does it dry out excessively, leaving no oil residue? When adding water to the fuel sample, does the water seem to mix into the fuel in a cloudy manner? All of these are signs of high amounts of alcohol in the fuel, which can be E85 or extreme usage of a fuel additive that contains alcohol.

Typically, a weak fuel pump or restricted fuel filter will be capable of supplying enough fuel to meet the demands of the engine at idle, but not when under the high demands of driving. So, in many cases, a fuel pressure test may pass at idle but fail while driving. It is also popular for the fuel pump to only become weak when it is hot. So continued driving may be necessary to find a weak pump.

An injector that fails to open at all times can be easily clued in on with a small shot of carb cleaner into the air intake manifold. If the engine smoothes out while the cleaner is added and resumes misfiring when it is not, then injector pinpoint testing should follow.

An injector that is leaking into the intake at all times may be spotted by a wet or blackened spark plug on one cylinder. But, it is important to note that multiple darkened spark plugs can simply be a result of the PCM richening the fuel mixture multiple cylinders in attempt to counteract the extra oxygen found in the exhaust from one misfiring cylinder of any multitude of causes.

Loss of compression to a cylinder will certainly cause a misfire. Most of the time, this will show up during a simple compression test. A “pooting” noise from either the intake or the exhaust can be a clue to a leaking valve.

If the “pooting” noise is heard from the intake, it is important to know that such a sound is normal on some vehicles as the IAC valve moves.

A bouncing vacuum gauge needle is a clue to a leaking intake valve, but may not catch a leaking exhaust valve. Charging the cylinder full of shop air via the spark plug hole, while on compression stroke can also reveal a valve that is not sealing. Coolant leakage into a cylinder can also cause a misfire.

Looking for things such as a coolant odor from the exhaust, fuel odor in the coolant and unexplained loss of coolant can be helpful. Use of “blue water” block testers and UV coolant dye (black lighting piston tops) are also helpful tools for this.

In some rare cases, there may be nothing actually wrong with any of the previously mentioned systems, especially in the case of a P0300 (random/multiple cyl misfire). If the engine oil is excessively overfull, the crank weights can slap the oil and set a code. Even a drive belt that is slipping intermittently can set a P0300.

The reason is that the PCM doesn’t “know” if a misfire occurred because it doesn’t actually monitor the combustion action directly in the cylinder. Instead, it measures the crankshaft’s rotation speed. It “knows” when it is each cylinder’s turn to fire, and it “knows” how fast the crankshaft is traveling between events. If it sees the crank slow down enough between events, it reaches for a misfire fault code.

Most of the time, a customer will not say their engine is “misfiring,” instead they will use words to describe the symptom in ways they can relate.

Taking the time to inspect the symptoms so that the appropriate system can be focused upon, then narrowing that to the suspect components, then lastly pointing the causal part(s) will help you maintain “courage under misfire.”