When I first began my automotive career way back in 1957, the symptoms of an ailing engine were very apparent. A carburetor with a worn accelerator pump, for example, would characteristically stumble on acceleration and a closed-up set of distributor contact points would cause the engine to become very sluggish. Low fuel pressure caused by a bad fuel pump or clogged fuel filter would cause the carburetor to lean out. High fuel pressure caused by a fuel pump with an incorrect pressure spring or a sinking carburetor float with normal fuel pressure would cause the carburetor to run rich. In those days, symptom diagnosis was just about as simple as that.

But times have changed, because symptoms and their causes don’t always have a direct correlation. Part of the reason is because operating strategies built into modern on-board engine management systems tend to distort and conceal the symptoms of a component malfunction. To illustrate, the PCM obviously compensates for a leaking fuel pressure regulator diaphragm by reducing fuel delivery to the engine. In the same sense, the PCM compensates for minor vacuum leaks by increasing fuel delivery. Each of us has seen engines that performed amazingly well with an EGR valve stuck wide open or with one coil not functioning on a three-coil distributorless ignition. Part of the reason might be an adaptive strategy built into the PCM’s software.

But times have changed, because symptoms and their causes don’t always have a direct correlation. Part of the reason is because operating strategies built into modern on-board engine management systems tend to distort and conceal the symptoms of a component malfunction. To illustrate, the PCM obviously compensates for a leaking fuel pressure regulator diaphragm by reducing fuel delivery to the engine. In the same sense, the PCM compensates for minor vacuum leaks by increasing fuel delivery. Each of us has seen engines that performed amazingly well with an EGR valve stuck wide open or with one coil not functioning on a three-coil distributorless ignition. Part of the reason might be an adaptive strategy built into the PCM’s software.

As for a manufacturer’s symptom diagnostics chart, most are too general to be of much help for the experienced diagnostic technician. What isn’t covered on a symptom diagnostics list are pattern failures. Pattern failures are usually most easily located in archival fixes, such as that maintained by the International Automotive Technician’s Network (iATN) or by similar archival data found on online subscription database services.

Three of a Kind

I recently had three nearly identical Ford light trucks illustrate how misleading symptom diagnostics can be. Although each of these vehicles is a Ford truck dating from the late ’80s to the early ’90s with relatively simple on-board management systems, they illustrate my point.

Two were equipped with the EEC-IV, MAP-equipped speed density systems that have no data streams or fuel trim numbers to assist the diagnosis. The third, a 1991 model, is equipped with an electronic mass air flow sensor and produces a rudimentary data stream. Each of these vintage vehicles illustrates the concept that, while symptoms continue to be valuable diagnostic aids, they can also become misleading diagnostic indicators.

The SLOW-GOING ’86 Bronco II

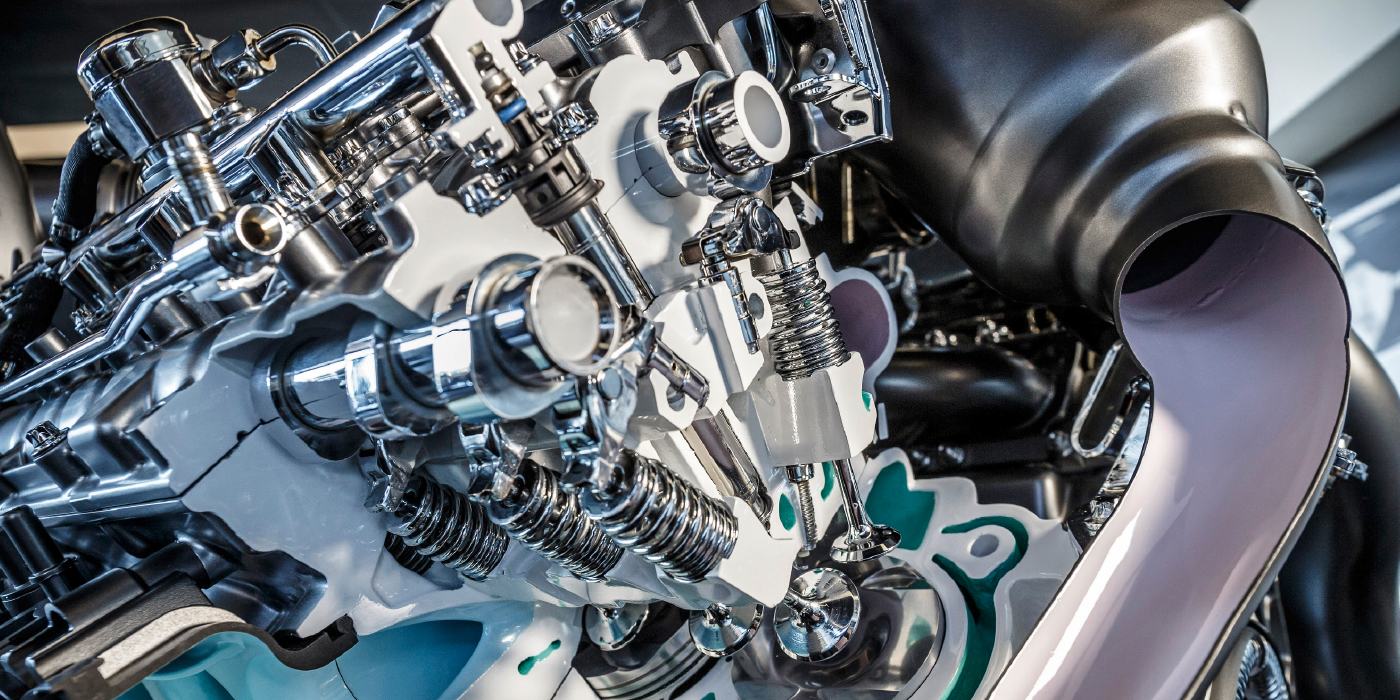

Let’s first consider the 1986 Ford Ranger equipped with the 2.9L fuel-injected engine and manual transmission that is experiencing intermittent cold starting complaints and a slight misfire at 2,900 rpm climbing hills. Another shop had brought the maintenance up to date with new spark plugs, wires, cap, rotor and fuel filter.

In regard to pattern failures, the old EEC-IV speed density Fords were notorious for manifold absolute pressure (MAP) sensor failures. In some cases, gel leaking from the MAP sensor can clog the vacuum line leading to the intake manifold and cause transient false MAP inputs to the engine control module (ECM). In rare cases, the MAP can “stick lean,” causing hard starting and poor performance. In even rarer cases, the MAP can cause a transient rich or lean operating condition.

For the latter reason, I still keep a new Ford MAP in my toolbox for use as a substitute component. Sure, the KOEO frequency generated by a Ford MAP can be tested and compared to an altitude chart to verify its accuracy. But the reason I substitute Ford MAP sensors is to eliminate a hard-to-detect transient MAP failure on a system with no data stream.

For the latter reason, I still keep a new Ford MAP in my toolbox for use as a substitute component. Sure, the KOEO frequency generated by a Ford MAP can be tested and compared to an altitude chart to verify its accuracy. But the reason I substitute Ford MAP sensors is to eliminate a hard-to-detect transient MAP failure on a system with no data stream.

Because the hard-starting symptom resembled a MAP sensor issue, I tested the ’86 Ford’s MAP sensor and found the required 138 Hz, KOEO, which is correct for our 8,000’ altitude. I blew compressed air through the MAP vacuum line to eliminate clogging and substituted a new MAP to temporarily eliminate the transient failure issue.

At this point, a road test was in order. Although the ’86 Bronco II’s engine started well, it did seem to have an intermittent rolling idle. During the road test, it experienced a light misfire at about 3,000 rpm as the owner had described. During the turn-around back to the shop, the engine stalled and would only start after flooring the throttle to put the ECM in the clear-flood mode. Clearly, the engine was intermittently running rich. After returning to the shop, the engine had developed a more noticeable, although intermittent, rough idle condition.

At this point, a road test was in order. Although the ’86 Bronco II’s engine started well, it did seem to have an intermittent rolling idle. During the road test, it experienced a light misfire at about 3,000 rpm as the owner had described. During the turn-around back to the shop, the engine stalled and would only start after flooring the throttle to put the ECM in the clear-flood mode. Clearly, the engine was intermittently running rich. After returning to the shop, the engine had developed a more noticeable, although intermittent, rough idle condition.

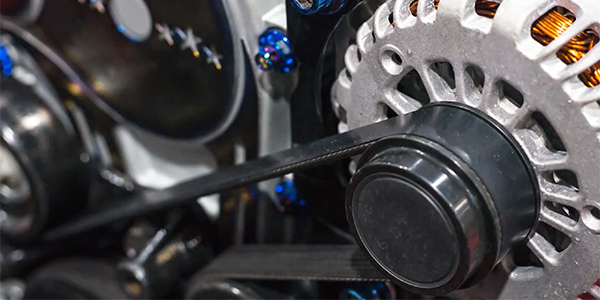

The first step in diagnosing a rich condition on an old Ford is to test fuel pressure and volume. Although the test indicated that the fuel pressure matched specifications, I repeatedly grounded the fuel pump test connection just to see if the pressure would remain the same as the pump cycled on and off. About the time I was going to give up cycling the pump, the fuel pressure test gauge pegged at nearly 100 psi, which is well over double the KOEO specification of 40 psi!

Quite clearly, the ’86 Bronco II had suffered another Ford pattern failure, which is an intermittently sticking fuel pressure regulator. With the original MAP re-installed, another test drive proved that the fuel pressure regulator, not the MAP sensor, had been causing the intermittent rich condition.

The Sagging ’91 Ranger

This 1991 Ranger, equipped with the 4.0L engine and manual transmission, stumbled badly during the first test drive on a cold engine. After warming up, the engine accelerated perfectly. Upon returning to the shop, the engine exhibited an intermittent, slightly rough idle. A light squirt of aerosol intake cleaner into the throttle body reduced the idle speed, which indicated that the rough idle was being caused by a rich, rather than lean, condition.

Because this engine is equipped with a MAF instead of a MAP sensor, I checked for debris that might disrupt or distort airflow through the MAF assembly. Speaking from experience, I’ve had everything from a piece of carpet yarn to a sunflower seed half-shell distort or restrict air flow through the MAF sensor housing! Once installed, the MAF sensor output voltage responded perfectly when tested with a lab scope. A fuel pump pressure test indicated that the pressure was well within specification, which seemed to eliminate fuel delivery as a possible suspect.

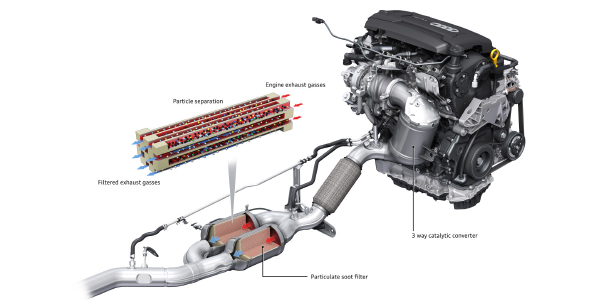

During a second test drive, the Ranger sagged so badly upon acceleration that it wouldn’t reach 30 miles per hour. Upon returning to the shop, the engine idled slightly rough, but wouldn’t accelerate past 3,000 rpm, wide-open throttle (WOT), in neutral. At this point, I suspected that the catalytic converter might be disintegrating and intermittently clogging the exhaust.

After removing the oxygen sensor and installing an exhaust back pressure tester, I again repeated the WOT test and the engine again wouldn’t accelerate past 3,000 rpm. The rather slow-moving data stream indicated an oxygen sensor voltage of about 0.700 mV at WOT. The back pressure tester indicated 3.5 psi at 3,000 rpm, WOT, which indicated that the exhaust had no appreciable restriction.

My first clue to the cause of the ’91’s failure to accelerate came as I removed the exhaust pressure probe. The tip had become coated with a thick layer of soot in just a few second’s running time. Clearly, the engine was running so rich that it wouldn’t accelerate. During the second acceleration test, the engine ran perfectly, touching 5,000 rpm in neutral. Now the sagging acceleration symptom had disappeared with no apparent reason. No reason, that is, until I noticed that the fuel pressure tester had pegged to nearly 100 psi! Unlike the ’86 Bronco II fuel pressure regulator, the ’91 Ranger’s regulator had caused a completely different driveability complaint.

The Rough-Riding ’87 Bronco II

The last in this series of case studies is a 1987 Bronco II equipped with the 2.9L fuel injection engine and manual transmission. The engine had just had the cylinder head gaskets replaced and had undergone a minor tune-up of spark plugs, fuel filter, distributor cap and rotor by another shop. A new set of ignition wires had been recommended, but the owner had declined the additional expense.

The owner’s complaint during my service write-up was a surging idle during cold start-up, a rough hot idle and a jerking sensation during low-speed acceleration. Obviously, with two fuel pressure regulator replacements under my belt, a sticking fuel pressure regulator became number one on my list of usual suspects!

But, regardless of how many throttle snaps and KOEO cycles I performed, the fuel pressure remained steady. Substituting a new MAP also didn’t change the intermittently rough idle condition. A squirt of intake cleaner actually reduced idle speed, so the problem seemed to be a rich air/fuel mixture, just the type I would associate with a bad fuel pressure regulator. So here I was, stuck with a rich rough idle and the MAP sensor and fuel pressure operating according to specification.

Being Out To Lunch

Lunch break is always a blessing to me because I have a chance to break out of my “diagnostic groove.” The diagnostic groove, in my case, was that, after finding two Fords with intermittently sticking fuel pressure regulators, I assumed that I’d find the same part causing a rough idle condition on this ’87 Bronco II.

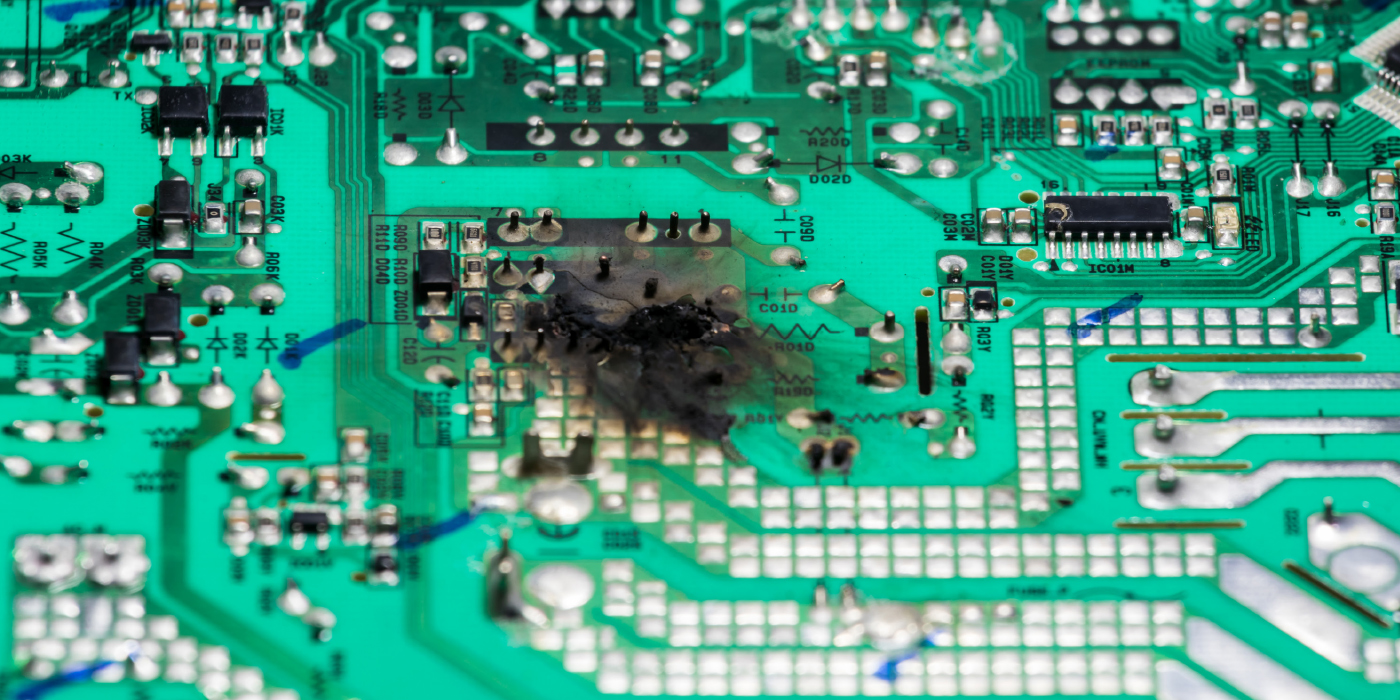

After lunch, I decided that I’d check the secondary ignition patterns to compare the fuel mixture and ignition in each cylinder. Upon starting the engine, the secondary ignition pattern ran clear off the top of the scope’s screen on all cylinders! Obviously, the engine had a bad coil wire. But, how could an open-circuit coil wire cause a rough idle and a rich air/fuel condition?

After substituting the 2’ long coil wire, I started the engine. Amazingly, it ran perfectly! Checking the patterns of the other cylinders, I found another open- circuit spark plug wire, which meant that the complete set of original equipment wires should be replaced.

A Diagnostic Summary

Going back to symptom diagnosis, we have three vehicles within five model years of each other, from the same manufacturer and with the same basic powertrain. The ’86 Bronco II suffered from an intermittent rough idle and mid-range ignition misfire. The ’91 Ranger experienced severe sag on acceleration and an intermittent, slightly rough idle. The rough idle was the common symptom, but the misfire and acceleration sag were two very different symptoms produced under the same dynamic operating condition. Both were caused by the same component, an intermittently sticking fuel pressure regulator.

The key to the equation is how each ECM is programmed to respond. My educated guess is that the fuel injectors on the ’86 Bronco II couldn’t deliver enough fuel to cause a severe sag on acceleration. The ’91, with a larger 4.0L engine and a MAF sensor, could evidently deliver enough fuel to create severe acceleration sag.

Although the ’87 Bronco II experienced the same basic symptoms as the ’86 Bronco II, the cause were vastly different. The ’86 model suffered from a sticking pressure regulator while the ’87 suffered from an open-circuit coil wire. The open-circuit coil wire, while causing a low-speed miss, was also causing a misfire on acceleration.

In this case, it’s important to understand that a misfire causes oxygen from the misfired cylinder to enter the exhaust stream. The oxygen sensor interprets this excess exhaust oxygen as a “lean” fuel condition and commands the ECM to increase the injector pulse width to compensate. Thus, the end result can be the same as a sticking fuel pressure regulator, which is a rich air/fuel mixture that causes a rough idle condition. While symptom diagnostics is always a good place to start, it can often become a journey that leads to a strange and unexpected destination.