You might take the mechanical components of an engine for granted when it comes to misfire diagnostics. Better combustion chambers, piston and valves do not fail or wear out like older engines.

Today’s engine management systems can recognize conditions that could be destructive and take countermeasures to prevent damage. But you should not throw out your compression tester and maybe invest in a scope and pressure transducer because modern loss of compression problems can be tricky.

Compression Testing

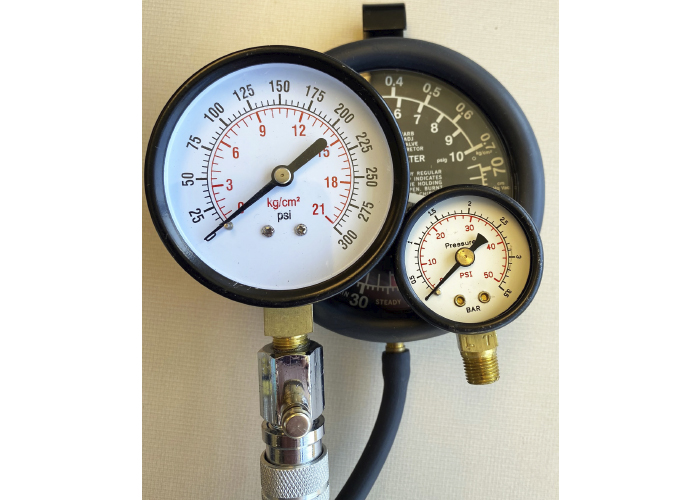

Compression can be measured with an analog gauge, pressure transducer or even current draw from the starter.

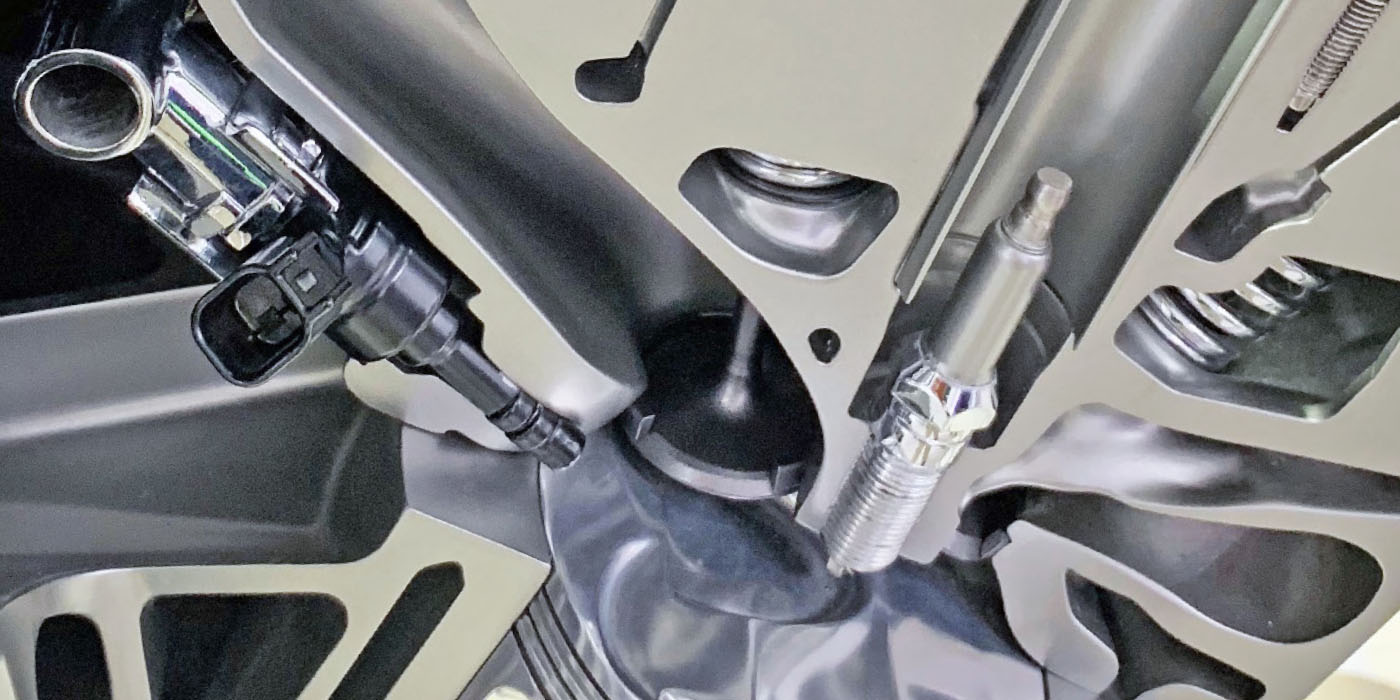

The “old-school” method of pulling the spark plugs and using a compression tester can help to measure and compare cylinder pressures. But an analog compression tester only measures the peak pressure.

Using a pressure transducer and scope shows you more information to analyze movement of the piston and opening of the valves. Also, pressure transducer diagnostics can be used for many diagnostic procedures, and many OEMs are including them in their service procedures. There are many classes covering the use of pressure transducers and in-cylinder testing online.

Relative compression testing with a scope can be used to determine if there is a loss in compression quickly. By measuring the current draw on the battery from the starter, the waveform shows the starter turning the crankshaft and the compression event inside the cylinder. If a cylinder has lost compression, the starter needs less power to turn the crankshaft during the compression stroke of a given cylinder in the firing order – the waveform will show a lower peak. If you use a second channel connected to a coil’s primary and know the firing order, you can determine the affected cylinder. But, if compression is low in all the cylinders, relative compression testing can be inconclusive.

Where is the loss of compression?

When a loss of compression in a single cylinder happens, you must first determine what is leaking. Gases from the combustion chamber can leak into the crankcase, intake valves, exhaust valves or past the head gasket.

A leaking head gasket is easy to detect using a tester to determine if there are combustion byproducts in the cooling system. Pressurizing the cooling system can reveal even more details about the condition of the head gasket.

If the gases are leaking past the piston rings, the gases go into the crankcase. While it is still a valid test to remove the oil cap or dipstick on a running engine to see if blow-by is excessive, it will not tell which cylinder is leaking. These can increase pressure inside the crankcase and positive crankcase ventilation (PCV) system. It is impossible to determine what pressures are normal. The specification is seldom listed in the service information, except if it is a warranty issue and contained in a TSB.

In 2016, BMW issued TSB SI M11 07 08 Mini outlined a diagnostic process from using pressure readings from a pressure transducer connected to the oil cap. The specifications Mini listed for the different engines ranged from 6mBar to 50 mBar. 50 mBar is equal to .7 psi.

This is where a pressure transducer and scope can help to look at crankcase pressures to determine which cylinder is leaking.

With a traditional leak down gauge that is pressurized with shop air, you can sometimes hear air from leaking exhaust and intake valves in either the tailpipe or intake manifold. This typically occurs in extreme cases where the exhaust valve is burned, or the intake valve is bent.

In cases where the leakage might not be heard with your ear, a pressure transducer in the intake manifold or exhaust manifold. This type of pressure transducer detects small changes in pressure. These sensors are essentially microphones. When the pressure changes due to four strokes of the engine and the movement of the piston and the opening of the valves, it generates a voltage that is displayed on a scope.

The Cause of Compression Loss

Once you know what caused the loss of compression, you have to understand why. Often a borescope or endoscope will let you see inside a cylinder, intake or exhaust manifold, allowing you to see any damage. But in some cases taking off the cylinder head or intake manifold might be the better option.

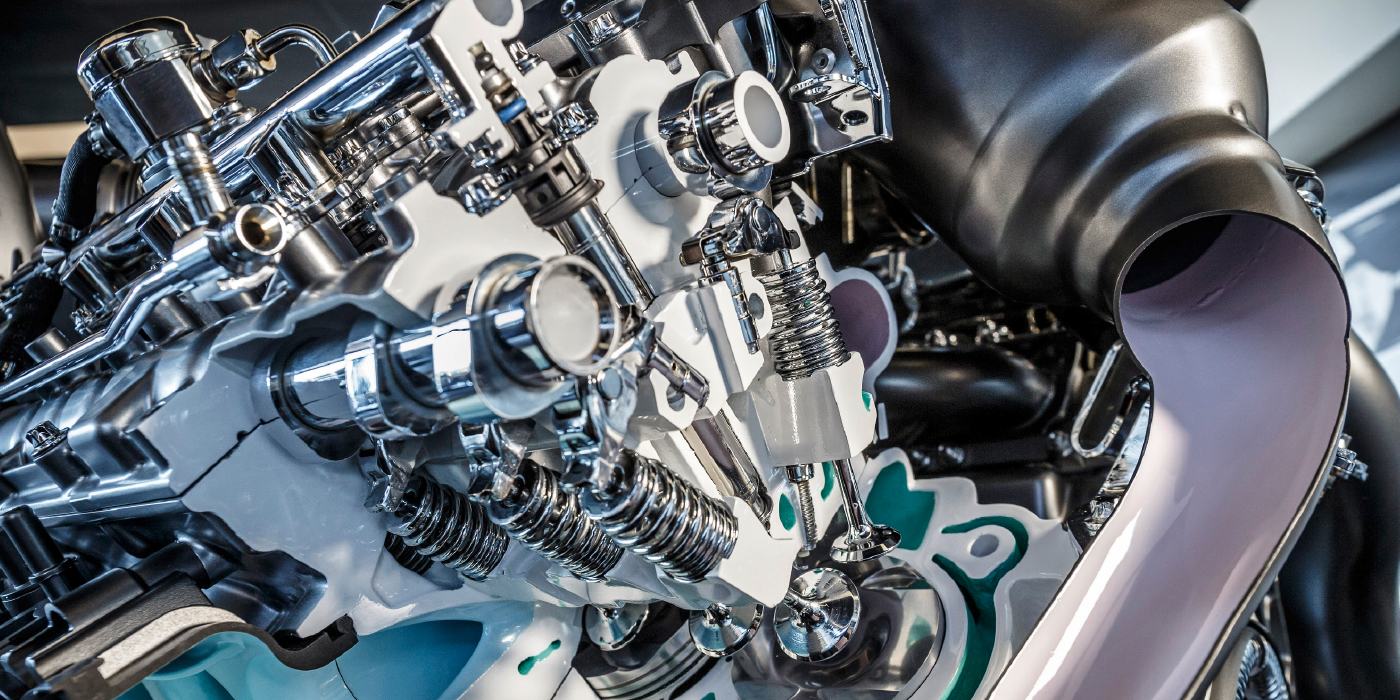

If the cylinder is leaking into the combustion chamber, the problem might come down to the relationship between the piston, rings and cylinder wall.

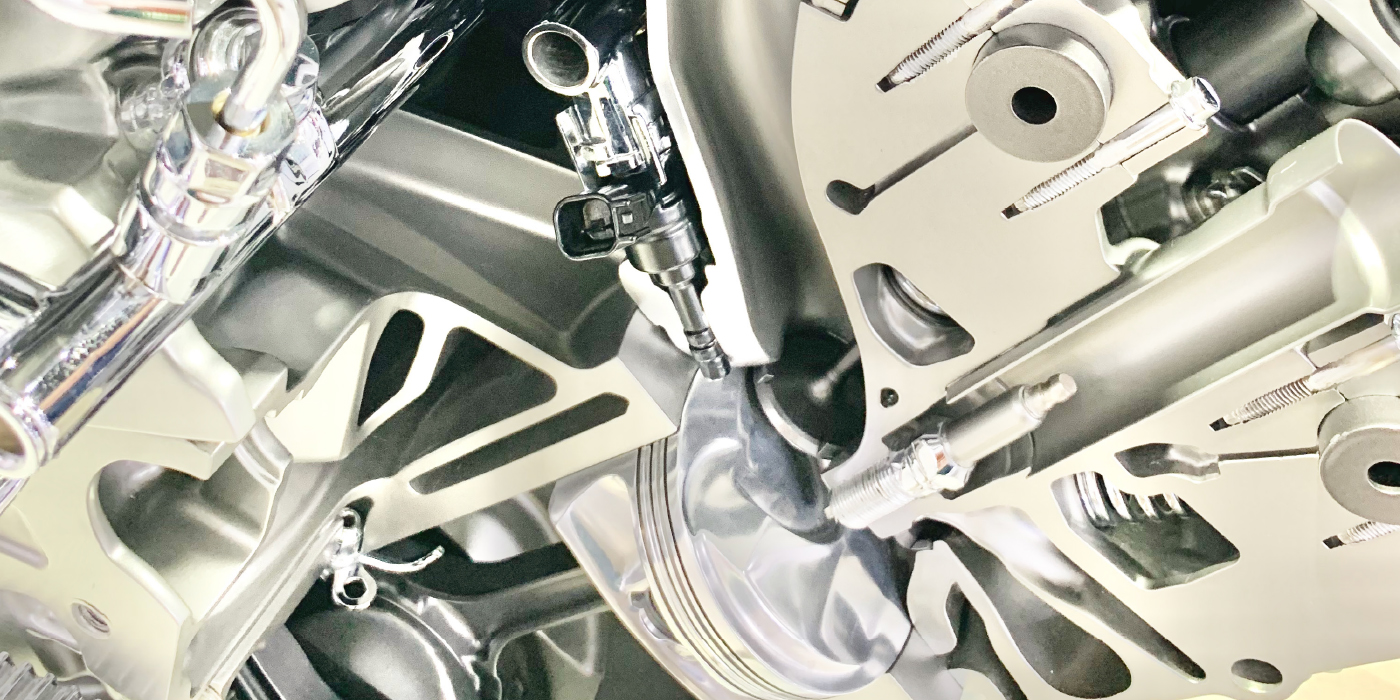

What has made modern engines reliable is how the piston rings work together with the cylinder walls. New finishes and piston ring designs manage the droplets from windage, oil jets and the connecting rod. Engineers have been perfecting these three components so there is not too much oil in the combustion, and the rings do not create excess drag. It only takes a few missed oil changes or the wrong oil to change the surfaces of the rings and walls.

When the loss of compression is limited to a single cylinder, the leaking compression could be caused by a pre-ignition or detonation. If the fuel and air mixture ignites before or after it was intended, it can be damaging to the piston and the lands for the rings. With many direct-injected engines with 11:1 or even 12:1 compression ratios, damage to a piston is possible.

During low-speed pre-ignition (LSPI) events, the air-fuel mixture ignites before the spark plug fires. This pre-ignition event can result in high cylinder pressures and engine knock. It can also damage the piston and spark plug. Some engineers call pre-ignition the “super knock” that can permanently damage an engine.

There are two theories behind LSPI. The first is that a hot spark plug or area of the piston ignites the fuel mixture early. The second theory postulates that droplets of oil are either deposited on the walls or trapped in the piston rings auto-ignite before the spark plug fires.

The second theory assumes that the higher compression ratio and forced induction create the “perfect storm” of a richer mixture and higher temperature/pressure that leads to the conditions that cause a pre-ignition event.

Exhaust valve damage is becoming more common as smaller engines produce more power. These downsized engines use higher combustion chamber temperatures for efficiency and power.

A cause of a burnt exhaust valve issue is typically found upstream with a malfunctioning fuel injector. An EGR valve blockage can cause higher exhaust gas temperatures on some engines.

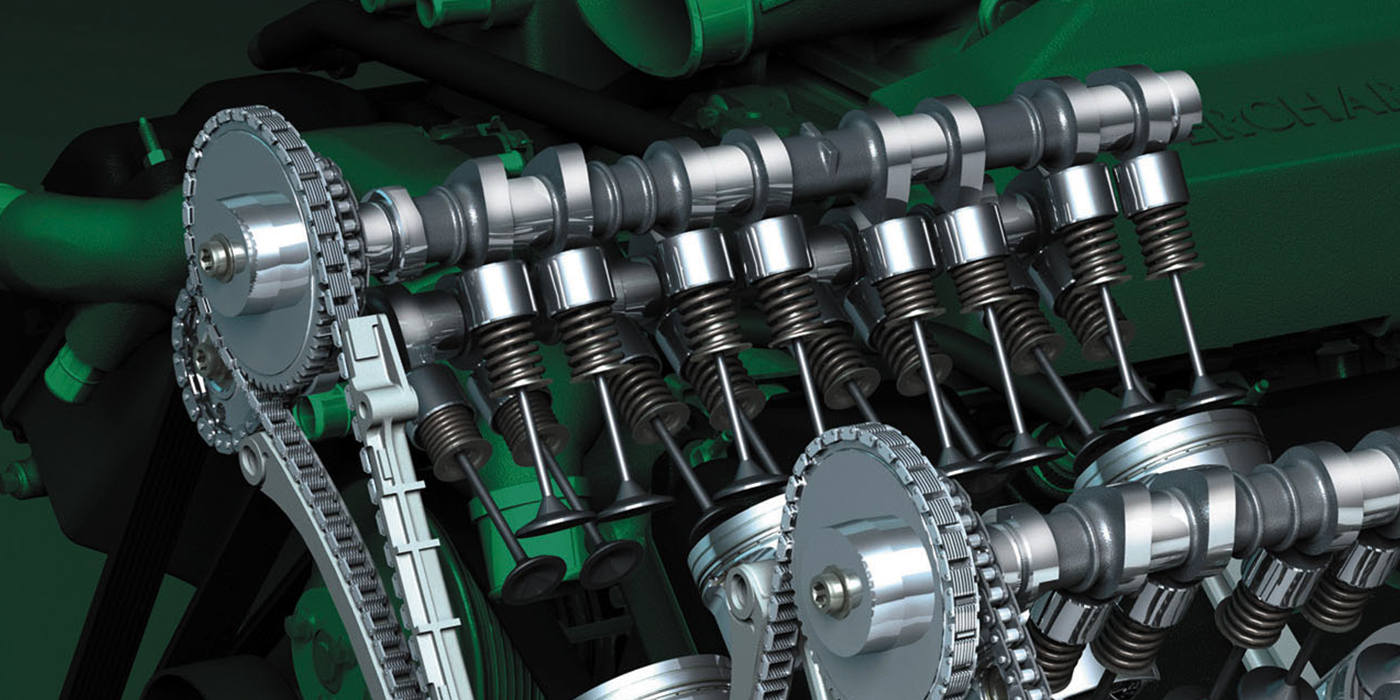

Intake valves can be damaged by foreign objects, carbon deposits, or a kiss from the piston due to a stretched timing chain or broken belt. On some direct-injected engines, carbon deposits from either gases in the cylinder or oil from the PCV system can cause enough blockage to prevent air from entering the cylinder and altering compression test results.

In the good old days, measuring compression was typically part of every tune-up. Reputable shops knew compression readings that were above 100 psi and even across all the cylinders, the tune-up would probably improve the performance of the engine.

If the pressures were off, they might offer to rebuild the engine with new rings and freshly honed cylinders. Today, the only option might be a crate or remanufactured engine.